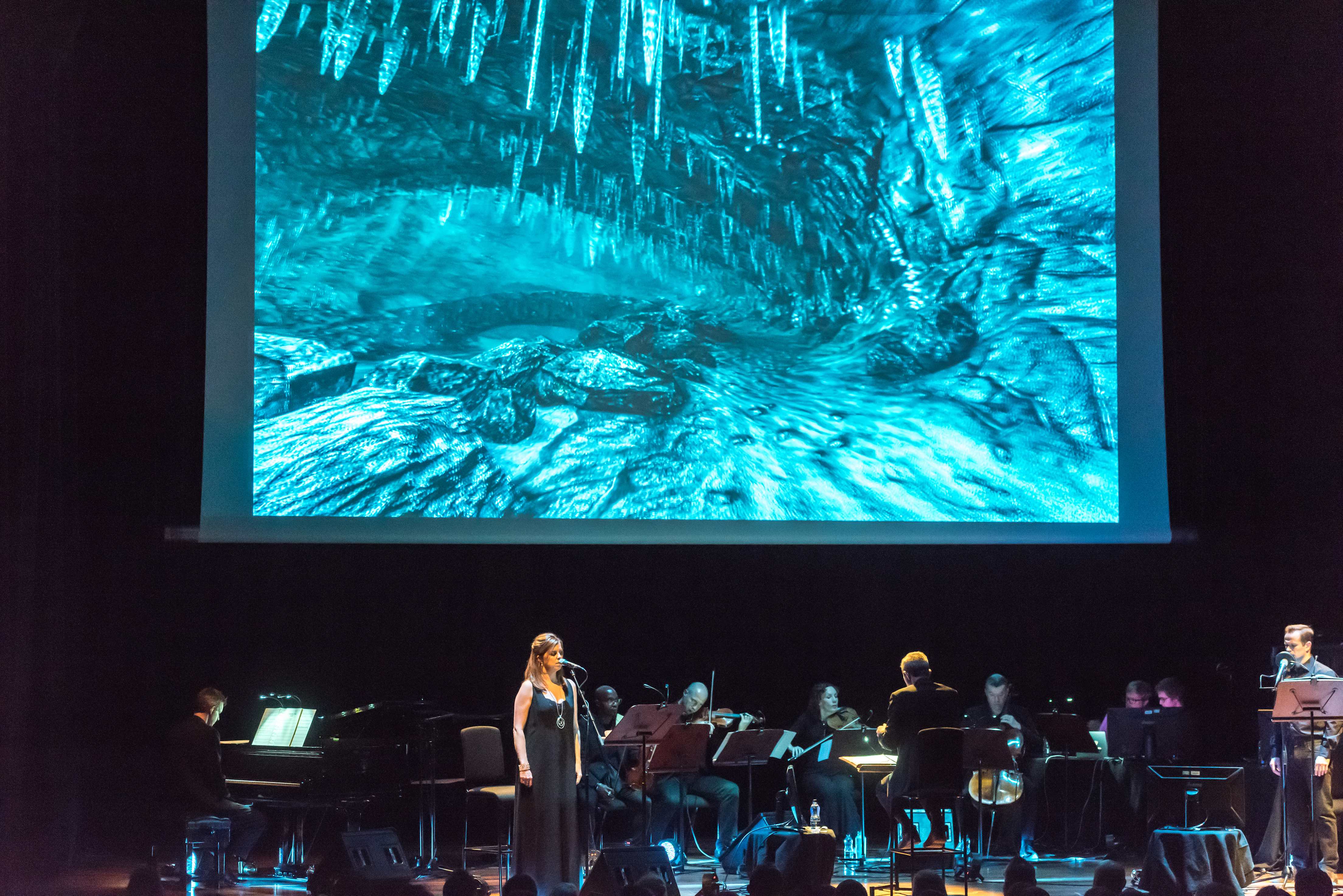

One thing is for certain: Jessica Curry is the definition of a pioneer. She has tested and redefined the limits of what it means to play a video game and the role of video game music. She is a BAFTA-winning, internationally-acclaimed composer of contemporary classical music, and is also the co-founder of celebrated games company The Chinese Room. Curry’s work has been performed in extraordinary venues, such as The Old Vic Tunnels, The Barbican, Sydney Opera House and Great Ormond Street Hospital.

The composer boasts an impressive career as a video game composer. She wrote the music for the genre-defying, BAFTA-nominated Dear Esther, which won awards for Best Audio at the TIGA’s and a GANG award. Her hair-raising and terrifying music for Amnesia: A Machine for Pigs was also multi-award winning, and her BAFTA winning music for acclaimed PS4 title Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture was named soundtrack of the year by MOJO magazine, sitting in the top 10 of the Official Charts for several weeks.

We had the pleasure and privilege of chatting with the vibrant Jessica Curry on her stratospheric career.

Jessica Curry, 2016

What is the composition process for one of your video games? How do you so perfectly capture the mood of the game and its surroundings?

When my husband Dan Pinchbeck and I started The Chinese Room together (he’s a writer and I’m a composer), our focus was never to make mechanically complicated games. We always wanted to tell good stories in interesting ways. Dan and I had done so much work together in different media (opera, soundwalks and installations) but we never really found a perfect home for what we were doing. Then, Dan made Dear Esther, and we were like, “Oh my god, this is it: this is where Dan’s writing should be and where my music should be”. It was so exciting having reached that point, after having worked together for so long.

Dan and I already knew each other really well. It is very important to have a collaborator whose work I truly admire and respect and that I’m inspired by. That’s why I’ve had such a peripatetic career, in that I don’t follow the medium, I follow the people. It doesn’t matter if it’s a piece of theatre or an installation, a film or a game. Dan and I just obsess over how to tell a story to the best of its ability and how to do it justice.

The other thing is time. Dan and I worked on Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture for three years together with the team, and I was writing the music from the beginning of that process. Still, in films and games, so many people are brought on at last minute. Sometimes it works, and sometimes I can really hear that there is no relationship between the music and what’s going on, and I find that really disappointing sometimes. I really enjoy settling in with the team, talking to the designers and the coders all the time. I’m not just responding to them. For instance, we’re working on So Let Us Melt at the moment, and sometimes the artists will have the music first. It’s very interesting to turn that traditional model on its head. The music is always a slave to the visual image, but we don’t do that in The Chinese Room.

When composing for video game scores, where do you find your inspiration from? Are there any other artists or composers who inspire you?

Dan really is an inspiration to me in terms of the stories that he tells, especially within video games. What I traditionally find frustrating is that the industry has this ability to create these extraordinary-looking, beautiful worlds with world-class composers working on the music, but actually, the stories, for me, are so… Infantile! I’m going to make myself really unpopular by saying this, but I don’t want to know necessarily about a fantasy world. I want to know about real people in real situations, and that’s what I think people in The Chinese Room do very well.

My first inspiration as a composer was Michael Nyman working with Peter Greenaway, because again, the music didn’t take that traditional, subservient role. Michael Nyman and Peter Greenaway wanted the music to be in your face, at the forefront of those films. I love Greenaway’s formal compositions. I think he’s a fantastic director. He achieves the most beautiful cinematography. I’m kind of obsessed with him. I did an interview recently where I was asked ‘If I had to choose one of piece of work, out of any genre that inspired me, what would it be?’, and I chose Belly Of An Architect by Peter Greenaway, because it’s such a beautiful, clever film.

I don’t come from a games world and I think it can be useful sometimes when you have people that don’t inhabit that medium because you don’t have the same preconceptions. You don’t say, “Well it has to be like this, because it’s always been done like this”. I came in with Dear Esther, and I didn’t know what I was doing! But, there are some advantages to that because I didn’t say, “Well, it has to be done like that, because that’s the way it is”.

My mum’s really inspirational. She’s a writer and left school at 15 and with no formal education. She always says to me that she wrote a play before she had ever read one. I do think it can be really helpful to be an outsider. Never be afraid to take on jobs where you’re not an expert. I know that’s contentious advice, but I think it’s okay to say, “I’m new to this. Maybe that means I can bring something new to it.”

Tell us about your soundtrack for Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture.

There’s so much going on invisibly in the music. The score is absolutely promoting the idea of the Anglican choral tradition. If you grew up in an English village, even if you’re not religious, (as Dan and I aren’t, but we both grew up in small villages) the Church is so integral to village life. It just permeates everything. I wanted the music to reflect the fact that we have Father Jeremy in the game, and the Church is so central in that world. I didn’t want to support the action, because so little goes on, but I wanted to create the ghost of a world. The world is already over when you start the game so I couldn’t score this world. The music is so nostalgic, harking back to this idea of a Golden Age of Britain that never actually existed. What I wanted to capture with Rapture is that sense of nostalgia for a world that is already gone. The player has that feeling of loss and melancholy as they’re playing.

The music is also providing emotional support but I didn’t want it to get too much in the way because I’m a great believer in silence in games. In everything I’m watching on television at the moment, the music starts at zero and then it’s scored through the whole TV series. I get really cross —I’m old— I shout at the telly. I just pray for space a lot of the time. That’s what we are quite good at doing at The Chinese Room: letting the player have their own emotional journey through a space, trusting that they can fill it with their own stories and interpretations. I never want the music to be just guiding them every step of the way. Sometimes, not having the music is allowing them to think.

At the moment I’m obsessed with Duruflé’s Requiem. I sang it last year in choir, and I think that was really influential on Rapture at the time, because I was singing it while I was writing it.

Your score for Amnesia: A Machine for Pigs is very dark and chilling. How did you approach writing this score? Did you ever get frightened during the process?

That was a dream of a game for me to score, and I wish we’d had the budget to record it with live instruments. It really is an example of soundtrack that badly suffers from the use of samples. One thing I’m considering this year is rerecording it with an orchestra because there is some really good music in it, but I’m not so proud of the score because of its technical limitations.

Thematically, it was great: Victorian London, dead wives… I got to use the glass harmonica and these obscure Victorian instruments and I got to write music hall music and German Lieder music. That turn of the century was such a fertile time, musically, and I got to incorporate all of that into the soundtrack.

What was going on at the time, and what is actually still going on (with the conservative government, the way the poor retreated in the United Kingdom, the way we’re just seen as commodities to governments and large corporations, etc.) is so enraging. It felt like there was so much political crossover, and it just felt like an absolutely perfect fit.

I really did scare myself, more with the soundscapes than the actual music. I wear these weird noise-cancelling headphones and people would come into my office (I can’t see the door or when they come in), they would just touch me on the shoulder to get my attention, and I’d be *dramatically mock-screams* screaming! The other thing that scared me is that we have a son, Oscar, and he sings on the soundtrack. I kind of wish I hadn’t done it in a way, because (spoiler alert) there are two dead brothers in the game. As a mother, I felt really superstitious about it.

The whole thing gave me nightmares. I gave up eating meat, because the game is so much about slaughterhouses. Dan and I had to do all this horrendous research on how pigs are slaughtered and you can never unsee those images once you’ve seen them! Bacon, also, became a thing of the past. Don’t watch those videos, if you love bacon! Remain ignorant! It was a hard game to work on because it was so extreme in so many ways… Politically, it was so dark as well. Actually, a lot of people missed that theme, because we are still not really a political industry. So many games are still frightened of tackling these political subjects.

As of April 22nd, you will present the UK’s first radio series dedicated to video game music, High Score, on Classic FM. What do you have in mind for this show?

I was so pleased to be asked by Classic FM because in every interview I’ve done, I always would say how frustrated I am that game music still isn’t taken seriously. A lot of snobbery exists around it. It feels like we are where film music was probably 40 years ago. Film music is so accepted now and we’re going through that same process. I’ve been trying to get there to be a Video Game Music Prom at the Royal Albert Hall, unsuccessfully so far. I think Classic FM have seen that I’ve been advocating very strongly for the game music scene and they’ve been really amazing and very supportive.

I’ve been working with my producer to work out what the six shows are going to be about. One show will be on “Worlds”, which I was really passionate about because I don’t think anything is capable of creating a world like a video game is able to. I’m doing a show on “Heroes and Heroines”. I have pushed for a show on “Women”, which is another thing that I’m very passionate about. The industry is still so male-dominated but there’s some amazing work by women composers being done in the video game scene. We will probably get much hate mail and threatening on Twitter, but I’m ready. One of the shows that I also wanted to push was an “All-Requests Show” because one of the things that I properly love as a video game composer is the amazing support of the community. There are so many people pushing for video game music. Every time I have a new soundtrack out, there are groups on Twitter advocating for me and my music. I really want to give that community a voice by asking them for their most beloved soundtracks, instead of me just saying what I think is the best thing to do for six weeks.

Classic FM is primarily a music show so I’m not going to be interviewing composers. But, (because I’ve married one) I am really lucky to know all the big people in the game music scene, so I’ve been emailing them, asking them what they want me to play, of everything they’ve ever written. Often, it isn’t their most well-known track, so it’s been lovely. Most composers are dead, in terms of classical music. You simply can’t ask them what is the thing they’re most proud of, or what piece of music they love and why. So, it has been fascinating for me to hear responses from those people about the stuff that they’re proud of. I’m going to be playing their choices as well. It’s really forward-thinking of Classic FM to recognise that there is this interest and passion here regarding video game music and to want to delve into that world.

In an interview for M Magazine published in September 2016, you spoke about the working condition for women in the game industry. It seems that the situation is slowly changing and improving. From your own experience, how do you perceive the future for women in the game industry?

It is changing more slowly than I would like. But I do have hope, in that we employ young women at The Chinese Room and they’re not waiting to be told that they have a place in the industry. They’re claiming that space for themselves, not in an aggressive nor a confrontational way, but neither are they waiting for permission. That’s the way we go forward as women: recognising and making clear that we have a right to be here, and not even questioning that right. Women are starting to form really strong networks with each other, and that’s the way to do it.

I was always really resistant to any sort of “Women in Game” movement, because I didn’t want to be a ‘Woman in Game’, I just wanted to be a ‘person’, a ‘composer’, physically in this space. But actually, there are really strong places for collaboration, support and promotion. I will always signal boost women, if I can. I’m not doing this show on Classic FM because I think there aren’t any really good female composers. On the contrary, I believe these people aren’t being given the opportunities at the moment, and I know there is fantastic work. If there wasn’t fantastic work, I wouldn’t still play that music.

It’s interesting that it’s a very ageist industry as well. We tend to focus on 30 Under 30 every year and the people with experience actually tend to be a bit put out to pasture. It’s an incredibly white industry still: we have massive problems in encouraging people of different races, ethnicities and backgrounds. Even in terms of being a developer, just having the finances to be able to do that and the economic background you come from is a big factor. So it’s about being thoughtful in all those areas, and how you recruit. Often, at The Chinese Room, we’ll take people with less experience because they haven’t had the opportunities to get the experience since nobody would give them the opportunity. It’s about employers being more thoughtful and forward-thinking, asking themselves what potential a person has, rather than what they have necessarily already achieved. I am really frustrated by the world at the moment… The industry still has a long way to go. It has the most horrendous pockets of mistreatment. But hopefully, these circumstances will create studios like The Chinese Room where we’re determined to do it another way and say that we can be economically successful: you can send people home at five o’clock who want to come to work the next day because you haven’t broken them and then burnt them out. It’s something I feel really passionate about, because so many people I speak to have such bad experiences.

Tell us about your next project So Let Us Melt.

I’ve just finished writing the soundtrack. I’m slightly scared because it’s so different to Rapture. I’m hoping that the people who love my music will come with me. It’s the first time I’ve written happy music in about 25 years! It’s been a shock to me because I’m so known for this melancholy sound that I love writing and that feels natural to me. After Rapture, Dan said, “We literally killed everybody in the world with our game… We need a break! We need a change.” He said, “I can’t write another tragic game at the moment. I really need to write something about life and living”, and he has done.

It’s our first game we’ve developed for virtual reality so that’s been really different. It’s for Google, and the soundtrack is kind of crazy. I have a disease that causes quite a lot of physical pain, so I was on quite a lot of morphine going over the soundtrack. I’m listening to it now that I am off morphine, thinking that this is slightly insane! But it’s really joyful. I sent it to my best friend, who always listens to my music first. I could hardly walk while I was writing the music, and she said, “Well, you may not be able to walk, Jess, but you can fly in your music”, which is one of the nicest things that anyone has ever said to me. That’s how the music feels to me: it’s full of movement. Both Rapture and Esther are so still, so it was lovely to write something that feels all about life and joy.

It’s a big set-change for The Chinese Room in general, so we have no idea how people are going to take it. But I’m recording at AIR Studios in a few weeks with some amazing musicians. We’re recording with the London Voices again and they’ll give it an amazing choral element, so I’m really excited. So Let Us Melt has been a fun one to do. It has also been different for us, because it was 12 months’ worth of development. We’re used to a much longer development cycle, so that had its challenges. The music really kept me going, through quite a difficult physical time, actually. Everyone who has listened to it so far has had a massive smile on their face, and they’re moving. No one has moved to my music, ever, before! That’s quite a big thing, people not just going like that *bows head in a melancholy way*.

Do you work with music differently in the context of virtual reality?

It was really different, actually. A lot of people have said to me that in virtual reality, the players are quite confused if the music is too full-on and too in-your-face because they can’t really locate where it’s coming from. I’ve chosen to completely ignore this advice. This is where we started: when I went to film school, they said that our music couldn’t be in the forefront, it had to be in the background, and then I discovered Michael Nyman. I kind of feel like I’m still there, in a way, saying that I’m going to challenge this. I don’t know if it’s going to make people’s ears bleed or make people sick. It hasn’t been a problem so far for play-testers. I didn’t just want to put the music in this ambient and neutral state, I wanted to push how far you can take putting music really in the forefront. It will be interesting to see people’s reactions to that as well.

What I do like and what is really important to us is that the Google virtual reality headset is sixty-something pounds. We wanted to do something that lots of people could afford to buy. That is again part of The Chinese Room’s ethos, which is to hopefully allow the democratisation of games to the greatest extent. We wanted many different types of people playing it. I think that’s one of the things that people hopefully like about us as a company. Everyone said that no one was going to play Dear Esther because they thought it was really difficult and the language is really challenging. Yet, Dan and I have teenagers write to us every day, saying how much they love that game. Don’t make assumptions, based on people’s age, about how intelligent they are and what they can take. It really really annoys me. So hopefully, So Let Us Melt is a game that everyone will be able to play.

I don’t know what my next job is at the moment, and that’s really interesting. What will the next big project be? Where will it take me? I always think to myself that I will never be able to write something as good as the last thing I’ve written, and then I go through this massive period of feeling really sorry for myself. It took me a lot of time to get over Rapture. So Let Us Melt is the first score where I think I’ve got so many people waiting, asking what the music is going to be. I am feeling the heavy weight of responsibility at the moment, I just hope people like it.

Interview prepared, conducted, transcribed and edited by Amalia Morris and Sylvain Pinot.

Edited by Marine Wong Kwok Chuen.