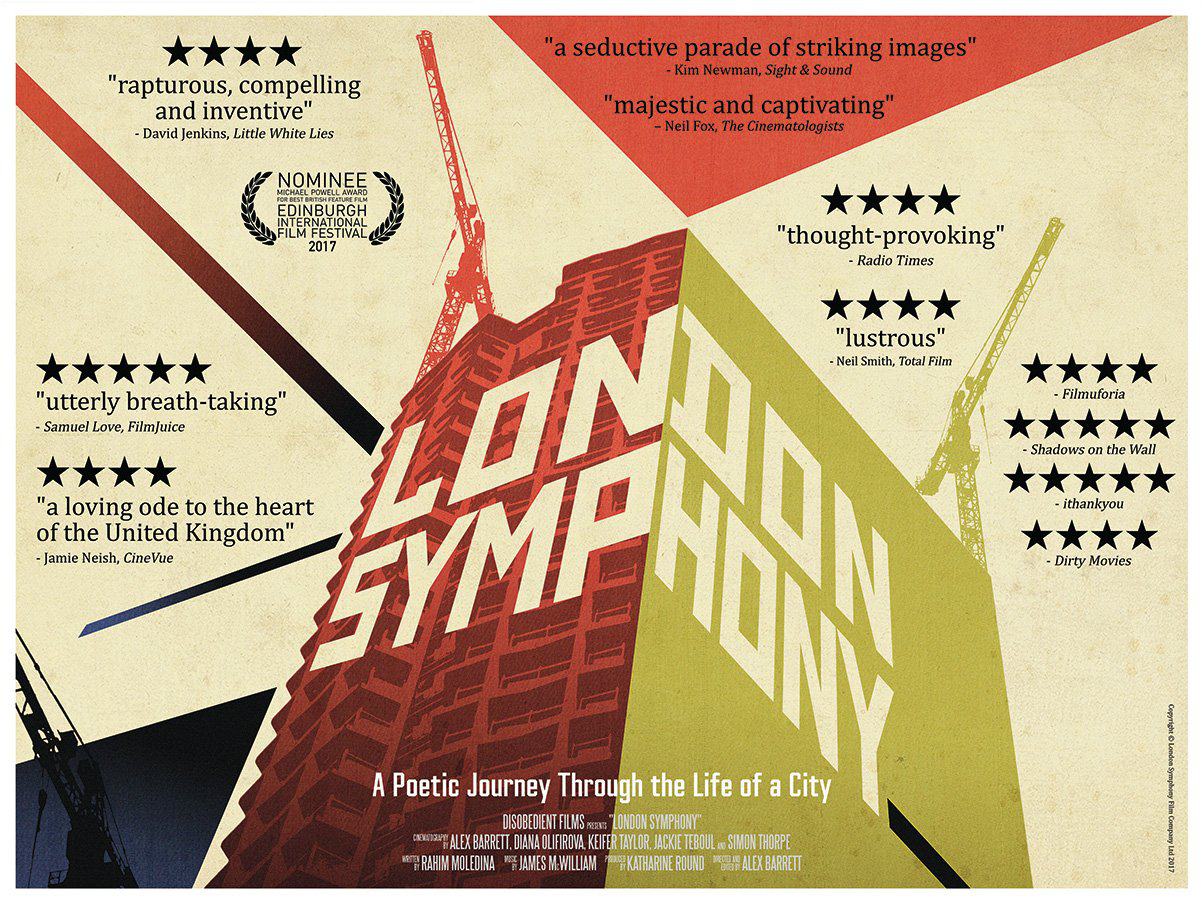

London Symphony is a city symphony like you’ve never seen or heard before. Alex Barrett’s inspired revival is light-years away from the industrial city symphonies of the 1920s. Divided into four broad sections the film takes the viewer on a visual tour of the city’s many features, from religion to nature, work to nightlife, in order to raise questions about our idea of community within urban space. A completely silent film, dialogue and commentary are replaced by James McWilliam‘s gorgeous orchestral score. The delightful music paints a poetic journey through the city of London and we for one, are happy to go along for the ride. The London-based composer, arranger and orchestrator, has composed scores for a multitude of mediums before this project with long-time collaborator Alex Barrett. McWilliam’s film and television credits range in style and genre and include Borgia, The Book Of Life, Crimson Peak, Mortdecai and Harry Potter & The Goblet of Fire.

Today, James McWilliam takes the time to chat with Score It Magazine and explains in detail what it really takes to compose a symphony.

Score It Magazine: How early on did you arrive on the London Symphony project? Did you know director Alex Barrett beforehand?

James McWilliam: I’d known Alex for several years before work on the film began, as we collaborated on a short film in 2009 that was similar in style to London Symphony called Hungerford: Symphony of London Bridge. In 2013, Alex phoned, saying he had the idea of turning the Hungerford short into a full feature film. We subsequently met on the Southbank, outside the BFI to discuss the project. He claims that he wouldn’t have undertaken such a project without me, but perhaps that was a ploy to get me to say yes!

Given the title of the project, I guess you knew from the start you had to compose a symphony, didn’t you? How much of challenge was it?

I certainly did and it was a challenge, but an exciting one. I had never written that much music for one project before but I couldn’t say no to such an opportunity. I decided to largely ignore the word ’symphony’ because of the musical baggage that the word carries and I was wary of writing a pastiche. Instead, I thought of it as a large-scale work in 4 parts, with an introduction and coda and tried not to think too much about what it means to write a ‘symphony’. I had a few false starts over the first year before the ideas that eventually became the final piece began to emerge. In particular, I found it hard to keep the continuity going. I wrote the piece over approximately 3 years in-between other projects and my daughter being born, so I had frequent periods where I was unable to work on it at all. When I came back to it I sometimes found it difficult to get back into the mindset that I was in when I left it. Something else that was always on my mind was just how exposed my music would be and the adverse affect this could have on the film. People can have quite objectionable opinions when it comes to music they don’t like, so I was acutely aware that my music could turn people off the film regardless of what they thought of Alex’s work. I like to think I avoided that particular pitfall but it was certainly an ongoing consideration as the score progressed.

Did you start composing before watching any footage?

Unusually for a composer, I was in from the beginning. The first thing I did was to create a musical structure for the film that we both followed. The structure was loosely based on a symphonic form and gave indications of timings, tempo and the general mood for each section. There was no temp music, it wasn’t that sort of project, so I effectively had a blank slate. That said, the music didn’t really begin to take shape until Alex had put together a rough cut of the film. As I saw more of the finished edit, the film inevitably began to exert a certain tone and pace over the music I was writing.

Were you given any direction regarding the sound of the symphony?

Alex and I were in constant dialogue with each other about our progress but to Alex’s credit, he didn’t get involved with the music in the way a director often might. We had mutual respect for each other’s work so we both did what we felt was right and I believe the final film is all the better for it.

Very concretely, how do you write a symphony? We sincerely have no clue! Do you sit down and think, or do you let the images carry you while you play around on a piano (or any other go-to instrument)? Do you try things with the orchestra?

My old composition teacher used to say there are as many ways to compose, as there are composers. Like all those who sit down to create something from absolutely nothing you have to find your way in and discover something that will unlock the language that will carry you to the end. I like to think of composing as a game but one of your own making; you create the rules by which you’re going to play and then you sit down and work out how to get to the end.

The main thematic material for London Symphony is based on the ‘Westminster Quarters’, a sound that Londoners hear everyday coming from the Palace of Westminster. I took this pattern and used the system of change ringing to create hundreds of melodic and harmonic variations that would form the basis of all the music in the piece. Much of the rhythmic and structural material is based on the word ‘London’ in Morse code. I find it difficult to talk about how I compose, because it’s done in quite a haze. Often when I look back at what I’ve done I have no idea how I got there, it’s certainly not a linear process that’s for sure.

Where did you record the symphony and with which orchestra?

We recorded the score live at the Barbican centre in London with Covent Garden Sinfonia, conducted by Ben Palmer.

Just like a symphony, the film is divided into 4 movements: the first one focuses on the architecture, on the restlessness and the past of the city; the second is more bucolic, focusing on parks, outdoor activities and food; the third one is more spiritual and intellectual and deals with religion, museums and students’ life; the fourth is more upbeat and shows the nightlife of the city, the different forms of entertainment that London has to offer. How did you work on each movement to reflect its themes? How did you capture the essence of London through the music?

The music takes a ‘big picture’ approach to London rather than looking at things in detail as the film does. It is intrinsically ‘about’ London but it can’t be anything but my own musical interpretation of what it’s like to live in London for me, which I have done for over 20 years.

The first movement has, at its core, various polyrhythms that embody the rhythm and pulse of the city, old and new. It’s chaotic and at times aggressive with many ideas colliding and bouncing off each other. The second movement, in contrast, adopts a tranquil mood including moments of playfulness as the film focuses on leisure activity, food and wildlife. The rhythms of the first movement are still present albeit in altered forms. The third movement presented a problem, how to deal with religion in the film. I was aware that my attempts to represent religion through music might be seen as contrived and ultimately insulting. My answer was to treat the different religions in the film as one broader subject alongside a simple musical idea, the sound of two bells striking, imitated by various members of the orchestra. This time, the theme focused on the timbre of the two bells rather than the pattern of notes. The fourth movement was always going to be similar to the first, a return to the rhythm and pulse of London. There’s a beautiful rain sequence that segues into nighttime and the music becomes intentionally lugubrious and mysterious.

From your experience, would you say that it’s harder to score a silent film like London Symphony because there’s no other ‘voice’ than your music to narrate the film?

I think that’s an interesting point. In London Symphony there are no specific characters or dramatic storylines that unfold, the film is ‘observational’ in style. The music does become the dialogue of the film if the viewer wants it to become so. Through the music it’s inevitable that I exert an influence over how a scene will be interpreted. I wasn’t writing a ‘typical’ film score here and the music doesn’t always sit comfortably underneath the film supporting the narrative. It frequently develops its own path, before sitting back to play a secondary role in supporting the film. To answer your question more specifically, what we’ve done is quite unique so there isn’t the usual pre-conceived notion of what a score for a film such as this ‘should’ sound like. Therefore, if it were not for the shear volume of music I wrote, then I might actually say it’s easier to score a film like this because there are fewer restrictions placed upon you.

This piece is obviously very centred around London. What affiliation do you have with the city?

Although a Yorkshireman at heart, London has become my home and I love it very much. Like most Londoners I have a passion for the city, an almost familial love, where you can hate it and be angry with it, whilst knowing it’s a large part of who you are. The city is evolving every moment and I’ve always found that exciting.

According to the Merriam Webster Dictionary, a symphony is a consonance of sounds, in other words, a symphony could be summed up as an assemble of different elements that work well together. Do you think that in times like these (Brexit, terrorists attack, extremists trying to pit communities against one another, etc.) a film like London Symphony is important?

Yes, I believe it is. Alex has said that he wanted to make this film because he felt there was a rise in divisive politics in the UK and that it seemed an appropriate time to make a film celebrating London’s cosmopolitan nature. I completely agree with this and arguably the situation has got worse since we began work on the film. We hope London Symphony allows the viewer to reflect on questions around diversity and community and to appreciate what a wonderful city it is and one that’s made all the better by its multiculturalism.

The film and the score have been screened and performed live at the Barbican and there will be two more live performances in London before going on tour. Will you be conducting with the orchestra on tour?

No. I do occasionally conduct but I’d prefer to leave it to the leader of the Covent Garden Sinfonia, Ben Palmer. After spending so long writing the music in complete isolation, there’s something quite magical about handing your work over to someone else and hearing how they interpret your creation

Can you tell us more about your upcoming project, Close with Noomi Rapace?

Close is about a top female bodyguard (played by Noomi Rapace), who accepts the job of looking after a young and very rich heiress. It all goes wrong, however, when the young girl’s compound is attacked and an attempted kidnapping takes place. The director, Vicky Jewson, and I have worked together several times and I scored Born of War, Vicky’s second feature film. She’s a fearless, young director with an ‘anything is possible attitude’ and it’s always exciting to collaborate with her.

Before I get to grips with Close, I will be composing the music for a new series on a streaming service that I think for the purposes of this interview has to remain nameless. I can’t say too much about it at this stage but it’s going to be a challenge, a very different one to London Symphony and I can’t wait to get stuck in.

London Symphony was released in the UK on September 3rd, and it is touring around a number of selected venues until February 2018. Further details here.

Interview prepared and edited by Priya Matharu and Marine Wong Kwok Chuen