Just like fellow Australian musician Warren Ellis, singer-songwriter-guitarist and film composer Jed Kurzel also started off in a band. Indeed, Kurzel was a founding member of the blues rock duo The Mess Hall, before opting for a more cinematic path. Yet, the talented music artist did not purposefully set out in this direction; he confided to us that it was curiosity that led him there.

Whilst playing in the band, Kurzel was already scoring his friends’ short features, and when his brother Justin asked him to score his directorial debut, Snowtown (2011), he accepted the challenge without really knowing where this would take him. Kurzel was probably far from imagining that his first film score would harvest a generous number of trophies for him to display on his mantelpiece, including the prize for Feature Film Score of the Year at the 2011 Australian Screen Music Awards. Since then, Kurzel has scored many films —including The Babadook (2014), his brother’s Macbeth (2015) and Assassin’s Creed (2016), Alien: Covenant (2017)—and admits that he has learnt the job gradually (and we confirm: rather successfully!).

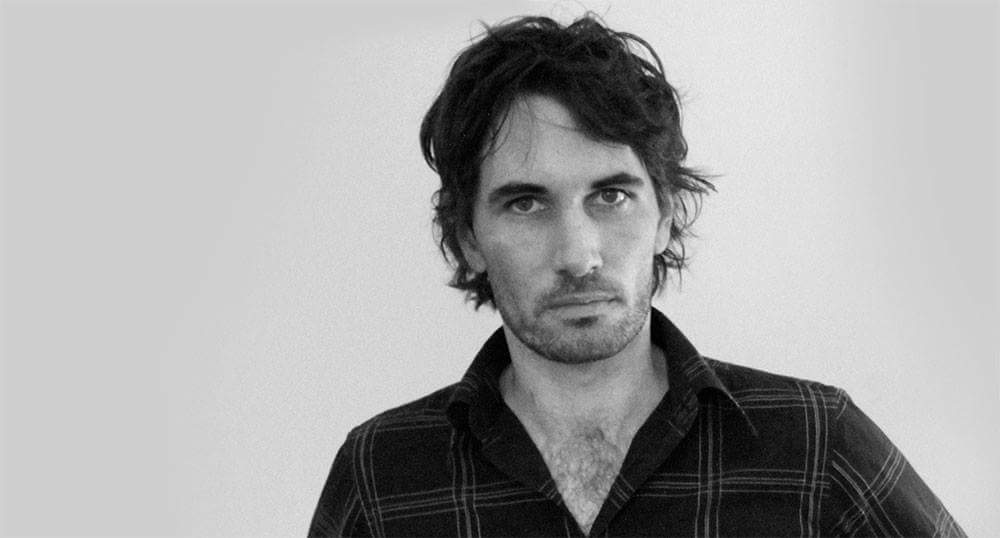

Jed Kurzel (Photo: Inside Film Magazine)

Finding a common denominator amongst Kurzel’s different projects as a film music composer may seem difficult at first. He takes on each project with a truly unique voice, with his method of selection steadfastly depending on the person with whom he will collaborate with, rather than the genre of the project itself. This ensures that Kurzel’s CV boasts a eclectic and vibrant repertoire, making him a truly fascinating musician to interview. We were lucky enough to chat with the man himself about his impressive career and dazzling achievements.

His lastest film is Kornél Mundruczó’s Jupiter’s Moon, selected in the Official Competition at Cannes 2017. The genre-defying film tells the story of a young Syrian refugee who discovers that he has supernatural powers after he has been shot while trying to cross the border into Hungary.

Jed Kurzel’s magnificent score brings beautiful depth to the rhythm of the film, fitting perfectly with its somber tone and stressing its tension whenever required. We had the pleasure of chatting with Kurzel about his creative process behind this score, and also about his eclectic and bold career choices.

Score it : How did you initially become involved with the Jupiter’s Moon project ? Had you seen Kornél Mundruczó’s brilliant previous film, White God?

Jed Kurzel : Yeah, I had seen White God. Kornél contacted me actually, and then we had a talk on Skype. Kornél likes to do everything face-to-face, so I ended up going over to Budapest and we spent a day together there. They hadn’t started shooting the film at that point, so I spent the day in the production office. Kornél had told me a lot of his ideas for what he was going to do in the film. When I got to Hungary, his cinematographers showed me some test shooting with effects that they had been doing, because a lot of the film was one take. It was amazing. And Kornél’s wife Kata was there as well—she wrote the screenplay. So basically, I got to sit down and thoroughly talk with them about everything and all the things that Kornél had mentioned on the initial phone call. Once he had showed me all the pieces and references, it all made sense. It was really exciting.

Jupiter’s Moon deals with a plethora of complex themes and is hard to put inside one single category. The film is a drama about the Syrian refugee crisis, it’s also a biblical allegory, it verges towards being a superhero film at times, it’s a thriller and there’s a bit of sci-fi. Moreover, it’s also a harsh piece of criticism of Hungary’s corrupt institutions… Did you find the right tone for the film immediately? Did the director give you any directions?

Because the film crosses genres so much, neither Kornél or I wanted to focus particularly on anything that would localise the film by using any music that was region-specific. We talked a lot about science fiction films and pushing the score into that kind of territory. In the initial stages, there was mostly that kind of sci-fi feel, so the score was mostly influenced by the sense of the ‘Other’ being involved in the film: “What is this energy that’s making this boy levitate, and how is he tapping into it?” Kornél and I were interested in what that sounded like, so we had lots of discussions about the different parts of that energy and how the boy can manipulate it. So, for example, if he’s angry, there’s a different sense to his energy. Kornél and I had talked about the feeling that the atmosphere was being ripped apart at some stages, and at other stages it felt incredibly beautiful and heavenly. That was where we were taking the score. Then, on the other side of that, we also wanted to bring in the emotional connection between Dr. Stern and the boy. We developed that at a later period with more melodic pieces.

Was there any temp music when you saw the first cut ?

No, he didn’t ever use any, which I was really thankful for. I came on very early before they started shooting. After they shot the film, Kornél and his film editor Dávid Jancsó sent me scenes, and then I started playing around. Kornél was adamant that he didn’t want temp music. He wanted the film to find the music and the music to find the film, as they were editing. That was great. I think too much temp music can be a trap that you can fall into sometimes.

Do you think your music has a unifying effect on such a complex film ?

I think so. It’s a film that crosses a few different genres, and in some ways the music glues it together. The great thing about the film, as well, is that the music is never in there as a wallpaper or anything like that. It has a very clear function. And a lot of the time, the music is in there and it is used very specifically: there is no dialogue. There are other films that I’ve done where the music is placed underneath the dialogue, and when you end up mixing the film you can hardly hear it under there. But with this film, Kornél made the music a feature which was really great.

Your music for Jupiter’s Moon is immersive and also adds to the tension of the story. It features a lot of percussion and seems to be rumbling, muffled sometimes, as if it were something waiting to explode… How did you achieve this effect, and which instruments did you use?

There’s a certain synthetic element to the music, which I guess is going back to the film’s sci-fi quality. We were conscious of that element being too much, so I mixed different experimental loops that I had put together, and then built the string section around that. So, it was basically an electronic string score. There is a lot of the percussion in the score with some strings cut up and edited in, and other music is played live. With regard to the rumbling sounds, that goes back to asking ourselves: “What is this energy? What is the only kind of frequency you can hear with it at times?” I think that’s why we put a lot of bass in there, like it’s rumbling up. Sometimes Kornél and I talked about it as if it were a beast that had been woken, and it just depended on what mood the beast was in when it was woken up. A lot of that alive rumbling came from that idea.

The Jupiter’s Moon score is very symphonic. Which orchestra did you record with ?

We were in Budapest. I’m not sure if we recorded with a specific orchestra, because they were coming in and out and rotating musicians all day. But it was great to be able to record out there and also to get a different kind of style of playing. I think those Hungarian musicians play on a lot of different scores, whether it’s for TV or film. So, it was lovely to have them rather than someone else to play on a Hungarian film.

You often work with Justin Kurzel, your brother, but some people would rather tear a limb off than work with a family member. What’s the routine when you work with him? What are the pros and cons?

We’re very lucky, we get along. Aesthetically, we have very similar tastes. I know a lot of people who don’t get along with their siblings and I can’t imagine how that would work. It’s great, because sometimes when you start a film with a new director that you haven’t met, it takes a month or so just to understand each other, and work out each other’s rhythms and aesthetics. In addition, you find yourselves kind of tip-toeing around each other, and finding each other’s strengths. But, when I’m working with my brother, it’s quite brutally honest. We can have an argument, go our separate ways, and then come back, apologise and keep moving on. We never harbour any ill feelings. That honesty is really a huge plus, because it means you get to the heart of something interesting. It can be detrimental in some respects as well, because if you are too close, then you can analyse things a little too much. I feel very lucky to have a relationship like that with him, artistically. We don’t need to talk a lot, either. A lot of the time with us, we’ll both be thinking of the same idea without having to express it to one another, which is great. Even when we’re watching something and it feels like it’s not working, we don’t need to really say anything or explain why its not working. For those kind of things it’s really good.

You come from a rock background and you were a member of The Mess Hall before choosing a more cinematic path. Can you tell us more about how you came into film music? Did your brother bring you into it?

It’s strange, because Justin was either just about to go to film school or had just started, and he began doing video clips for us and making short films. Outside of the band stuff, I was making music at home just for myself. No one was really hearing it except for Justin. He would come round and I would just play him stuff. By the time he was making his first film, he was saying to me, “You know all that stuff you have been making at home? I think you’d be able to make a score for this”. I was a bit terrified of the prospect, thinking: how do I do this?. But, I think that became a real bonus for Snowtown (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sJY6X8utM8A) because we were naive. To us, there were no rules at that point; we were going on instinct. I’d love to do that now, but I think the more things you do, the harder it is to make things by instinct. But, I kind of fell into it through Justin.

Previous to that, when I was playing in a band There was a television show in Australia and they needed a couple of songs written, and I wrote two for them. They then asked if I’d be interested in scoring a series, and I naively said yes, not really knowing how much work was involved! I got a real crash course in scoring, I really had no idea what I was doing. I had three months, and I can’t remember sleeping much. There was just so much work, there weren’t enough hours in the day to finish everything. I feel that was a really amazing working experience.

Let’s talk about Macbeth. It is a chilling film with its principal theme devoted to the supernatural: black magic and the power of fate. How did you attempt to create this eerie atmosphere with your score?

I worked with The London Contemporary Orchestra for Macbeth. They’re a very young orchestra who are really up for trying anything. I had just done a workshop with three of them: a violinist, a violist and a cellist. We went in with a few different ideas, and I sat down with them and explained what I was after.

At that point, Justin and I had decided that the witches, the landscape’s energy and the idea of the surroundings being cursed were all things we should explore musically. We wanted this feeling that, as the camera moved a bit from left to right, you could almost see the band playing this music. It felt like it was literally that organic.

In order to achieve that rustic, earthy sound, there was a lot of detuning of the instruments. I don’t think a lot of string players like doing that because it can harm their instruments, but these guys were so into it. They were detuning their instruments and playing a lot of different techniques: a lot of tremolos and then the crescendos. My feeling on that was to try and get a big sound with a smaller section. Even though the sound still has weight to it, you can still hear the nuances of individual players within the section. That made the music sit nicely within the grip of the landscape.

Macbeth was a really special score to do, because it took us a long time to find. Originally, I did a sort of electronic score for the film, which was sitting on the film for ages, through the edit, and then we threw the whole thing out and started again. I’m glad we did. When I see that film now, I think it’s one of those wonderful film music experiences when sometimes, magically, the score would sit really effortlessly with the film. I’m always looking for that kind of things to happen. They’re almost like mistakes that happen to work. You don’t really understand why they work, but you don’t really want to question that either because it’s just kind of special.

In your score for the film Slow West, both the ‘Jay Alone Theme’ and its variation are particularly haunting, with the use of violin and cello only. How did you manage to write a theme that corresponds so well to Jay’s character in the film? Do you have any routine when translating a character’s mood into a score?

No, that was more a discussion with John, the director. He is a musician himself, since he was in The Beta Band. That was great, because immediately we had a dialogue and a shorthand that was established early on, so we didn’t have to explain things too much. For the ‘Jay Alone Theme’, all he wanted was a waltz and a melody that he could whistle. Outside of that, we then asked ourselves: “Who exactly are we following here?” It wasn’t so much the landscape, but it was more Jay. We were then looking at Jay’s background, and we concluded that we wanted more of a Europeanness about the music, so that it wasn’t American. We also wanted to steer clear of all the western tropes. That was one of those compositions that came really quickly, over the course of a few days. I did that score in three weeks, and I always think that that is going to happen every time, and it never does. So, I was really lucky. Like I was saying before: the less you think, the easier it comes. But the hardest thing is to stop yourself from thinking too hard.

I like the way he used other music in that film as well, like the Congolese music and a lot of the folk stuff. It worked really well, with all these different forms bouncing off each other. But in that way, it reflects the melting pot which was the West at that time. What hadn’t been seen in film before was how diverse the community was at that point. It wasn’t just Spanish, or people coming from one region. That was also a big thing for John Maclean, the director.

You’ve scored three films that came with a lot of baggage: Macbeth (2015), with its multiple adaptations, Assassin’s Creed (2016), a beloved video game franchise adaptation and Alien Covenant (2017), the last opus of a 40-year-old franchise which has been scored by Jerry Goldsmith and James Horner, among others. How did you free yourself from the past in these cases?

That’s a great question. I remember studying Macbeth, and that felt like a really big weight. Everyone knows the play. It has been done in so many different ways, and there are some very famous scores and operas. That can hamstring you in some ways, because you are really desperate to try and find something new, and in wanting that so much you just don’t get it. I’m a firm believer that with music, the more you want something and the more you try to make it, the less likely you’re going to get there. With anything that I’ve done that is interesting, it felt almost effortless, rather than saying to myself, “Now I want to make this, and then I want to do this.” I was always trying to get to that point with Macbeth, and it took a long, long time. So yes, I definitely felt pressure for that.

With Assassin’s Creed I didn’t feel the pressure so much, because I wasn’t a gamer and I didn’t really listen to that music at all. For me, the scoring process was more about finding what the music would be for that film, rather than having anything to do with the series.

Alien was different, because we decided early on to use the Jerry Goldsmith themes in there, so in some ways that was a great launching-off point from where I eventually took the score. But, to be able to use some of those original themes was really good. I also love that score, so it felt to me more like, “how do I honour this without s******* all over his great work?” So, that was a totally different type of challenge, which I really liked.

But out of those three, I felt I had the most pressure with Macbeth, due to the baggage of that play.

You’ve scored films spanning over different genres, including Western, sci-fi thriller, psychological horror, video game adaptation and crime drama… Is there a genre you like best or that is easier to tackle?

It’s funny, because I have never really chosen a film based on its genre. It’s only now, looking back at what I’ve done up to this point, and I think, wow, I have done a whole bunch of different genres! But to me, a lot of the time I choose what I do depending on the director and the script. I don’t tend to sit there and think, I haven’t done a Western, I haven’t done this or that. For me, it’s more about whether I feel like I can have a voice somewhere, in with all the other voices of the film.

Can you tell us about Benedict Andrew’s Una and your other upcoming projects?

I’m not sure what I’m doing next, I’m still working out what I’ll be doing. My brother has got another film coming at some point that hopefully we’ll be doing, which is really great. I know Jennifer Kent who directed The Babadook has a film coming up as well.

Benedict and I actually went to university together in Australia, so I’ve known him for 20 years now. When he decided that he was going to make a film, we met up, I read the script and had some ideas about what to do, and it went from there. That same sort of thing happens with most directors. It was really challenging doing that film, because it’s based on a play, so it’s very wordy. The issue musically was figuring out how to take it out of it being a theatre piece. It’s difficult doing music in theatre on a very general level, because you have to be able to hear the actors speak. If there’s too much going on underneath the dialogue, it can sometimes get lost. That was the challenge that Benedict had: how to transfer this stage play to film. I think he was also liberated musically, because there is so much more you can do with music in film as opposed to music on stage. With that film, we were going for an atmospheric score that was appearing through the Ether. We talked a lot about memory and shimmering things, for instance when you’re looking at the desert horizon and it feels like images are either there or they’re not; everything is in and out of focus. It relates to the idea that when you get older, and you think back and reflect on memories, some are really clear and others are too far back to really hold onto.

Interview prepared, conducted and transcribed by Amalia Morris and Sylvain Pinot.

Edited by Marine Wong Kwok Chuen.