Who will be the successor to Avril & Monthaye (Lastman) and Sophie Hunger (My Life as a Zucchini) as winners of Best Soundtrack at the European Animation Awards? This year, there are more nominees – 5 for each category, instead of 3 last year – which means more possibilities and, let’s hope so, more surprises! One thing is for sure, the 2018 contenders very much raised the quality standards compared to last year. Score It Magazine talked to this year’s nominees for Best Soundtrack in order to know them better and explore their work.

I loved the soundtrack to Lastman, composed by Fred Avril & Philippe Monthaye. Its crazy 80s sounds with pumped up synths filled my Jean-Claude Van Damme fan heart with joy and energy – not to mention that the series is as crazy and exciting as the score is. I loved the original score composed by singer/songwriter Sophie Hunger for My Life as a Zucchini – pretty much everything has already been said about it, to such an extent that it needs no introduction. But the thing is, everybody expected them to win in their categories – Best Soundtrack for a TV/Broadcast Production and Best Soundtrack in a Feature Film, respectively – and they both did. This year, the EAA mocked the expectations, adding two more contenders in each category – and what a treat! From the musical flights of emotion in Darren Hendley’s score for the short TV film Angela’s Christmas to Dimitra Trypani’s instrumental experimentations in TheOx, a huge range of styles and techniques are represented this year, proving that animation is the best place where the artists’ imagination can prosper.

Artistry and activism

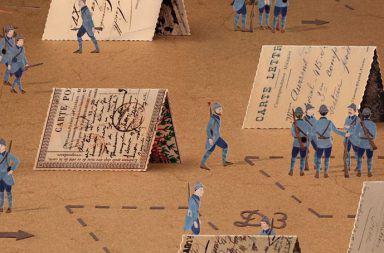

Composer and music producer Fridolin Nordsø, a first-time animation composer, was given the opportunity to do ‘really big stuff’ with his EAA-nominated score for The Incredible Story of the Giant Pear. The Danish composer’s recent work in scoring include the outstanding drama Ride Upon the Storm (Herrens Veje), might even have liked it more than he could have imagined: ‘It offers such space for your imagination! […] On Herrens Veje, I got to explore many things but always with the same emotion. Meanwhile a film for kids has all the emotions in it. I love that!’ Well, if there is something that is for sure with animation, it is that it can make any artist feel like a child having fun, even with adult-oriented projects. And the pair of composers composed by Yan Volsy and Pablo Pico – simply called YeP – knows something about scoring films for both kids and grown-ups. Last year, the two were already nominated at the Emile Awards for Fresh Out of School, a score they composed with fellow musicians Julien Divisia and Frédéric Marchand, and they are now coming back with a TV film for adults, A Man Is Dead, which gave them the occasion ‘to explore deep, serious tonalities in a dark universe’.

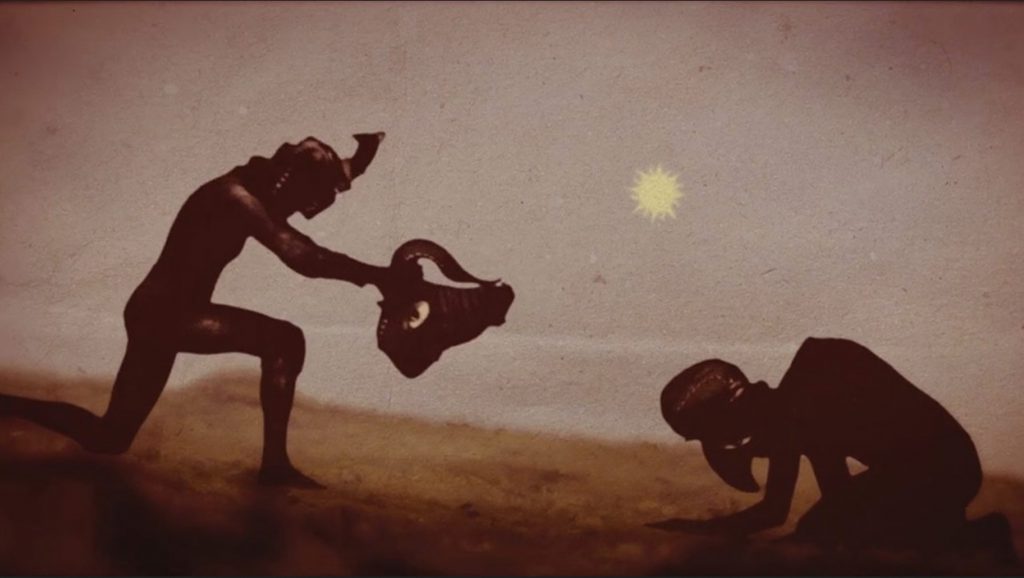

Black is Beltza. Directed by Fermín Muguruza. Music by Fermín Muguruza and Raül Refree. All rights reserved.

Based on the 2006 comic book of the same name, the TV film tells the real-life story of French filmmaker René Vautier and the making of his lost documentary short A Man Is Dead, in the spring of 1950, after the shooting of a worker by the police during a protest demonstration. About children and adults, Pablo Pico recalls that they primarily ‘work for a film or a project before we even think about who is going to see it’. Of course, there are as many ways to think and conceive a score as there are composers. But when it comes to a political film, you have to embrace the cause and support the message. This is what Volsy and Pico did with their score, inspired by popular French music and featuring instruments such as the accordion, the acoustic guitar or the double bass. ‘We wanted to do something acoustic’ that would ‘be a real modern creation, but we didn’t want it to be disconnected from the film.’ The result lies in a score that is simple in its instrumentation, straightforward in its themes and melodies but, above all things, it captures the charged atmosphere of the time and the shadow of the workers revolt – an although you can identify the score from its French roots, there is something with A Man Is Dead that refers to 1960s Italian communist cinema like the early Bellocchio and Bertolucci films.

Basque composer Fermín Muguruza is also heavily involved with political and social issues: the punk and ska musician composed, with his friend of 18 years and collaborator Raül Refree, the soundtrack to the crazy animation feature Black is Beltza which deals with both Spanish traditions and racial discrimination in 1960s New York. Way more than a film, Black is Beltza is Muguruza’s very own project: first a graphic novel published in 2014 and accompanied by an exhibition that has been touring Spain for the last four years, now followed by the film, its soundtrack and even a documentary. ‘The commitment to reality and situations of injustice has been a constant’ in his career, Muguruza tells Score It Magazine. Since the beginning of his 35-year old career in music, the musicians says, ‘the proposal I have made about anti-racism and the need for a dialogue between cultures is still more necessary than ever’. And if he regrets the failure of seeing a ‘dialogue between cultures’, he creates his own in the score for Black is Beltza, which summons African-American culture with a touch of Spanish and Mediterranean flavour added in the mix. Though he speaks many artistic languages, his mother tongue remains music and the Tarantinesque style of the film continues in its very punchy score: not only was there a need for music ‘to propose a musical journey’, but the score had to ‘convert music in a complementary narrative line’. And the music applies indeed its own language to tell its own version of Black is Beltza. From a cover of the Otis Redding anthem Respect sung in Basque by Fermín Muguruza himself with his former punk rock formation Negu Gorriak, to the collaborations with ‘musicians like Manu Chao and Ana Tijoux’ but also Boots Riley and Spanish pop sensation Rosalía, the soundtrack is somewhere between Tarantino and Spike Lee, under a watchful eye enriching the film with a fresh European consciousness, which implies that everybody is entangled in this fight. Hopefully, Black is Beltza will move people and things but Muguruza keeps spreading his message. ‘The struggle continues.’

Acknowledging musical experimentation

Quite often, awards ceremonies go hand in hand with the limitation of risks. The EAA, to say the least, offer quite an unexpected variety of contenders. Greek experimental feature film TheOx, directed by Giorgos Nikopoulos and which features a score by first-time film composer Dimitra Trypani, is one of them. A combination of live action performance and animation, TheOx is a curious yet gripping trip to experience. Trypani, a composer and lecturer at Ionian University in Corfu, works on interdisciplinary performance with music and video. ‘Giorgos Nikopoulos, who knew my work, thought that something might work if I would write music for pictures for once, and not use pictures on my music’, she tells Score It. Although ‘sound design is a separate element’ from the score, the two intertwine and get into a strange dance, pretty much echoing the actors’ moves. Building a score such as this one is the result of a lot of preparatory work. Trypani ‘sat down’ with Nikopoulos ‘and discussed the film almost minute by minute and what he thought about it, which sounds he had in mind in any way he could’. Going along with this almost-silent film from the very beginning to the very end, the music spreads its notes and sounds in Nikopoulos’s universe like the voice of a narrator would do, except that this narrator seems to come straight out of a nightmare à la David Lynch. And don’t even think that the composer used synths, electronic instruments or any form of technology: ‘I adore acoustic instruments, and if I can have the effects I want from natural sounds, this is what I’ll do.’ The score, which she defines as ‘a hybrid between contemporary classical and film music’, contains indeed many effects: buzzing, clicking, blowing sounds, you name it. ‘It’s 100% natural instruments’, she ensures. ‘The instruments offer you amazing opportunities, she continues, they can create the illusion that you are listening to something electronic while it’s just air blown through a flute. […] This is the key to creating much more three-dimensional sounds.’

But experimentation in film music remains the ideal area for electronic composition, and Marcel Vaid might know one or two things about this. The 51-year-old Swiss composer is the leader of Superterz, a collective of musicians who explore the possibilities of electroacoustic music with total freedom. Also a film composer for about 20 years, Vaid earned his EAA nomination this year for the score he composed for Anja Kofmel’s animation documentary Chris the Swiss, trying to throw light on the death, in the early 1990s, of the director’s cousin, a war reporter. Like Trypani and Nikopoulos, the Chris the Swiss composer and the director ‘worked very close. We listened to a lot of music together, sended each other films and music, we went to concerts’, Vaid says about their 2-year professional relationship. He was given the opportunity to do musical experimentation with a choir, something he planned to do ‘from the beginning’. And he gave himself carte blanche. ‘I wrote sentences that Anja and I sang and recorded. Then I reversed it on the computer and gave it to the choir, who learned to sing it in reverse. I then reversed the recording of the reversed choir so that the sentence is right again’ but, of course, with a strange feel to it, and ‘a weird sound in there’.

When I made a comment about how close her score sometimes was to sound design, Dimitra Trypani categorically replied that in TheOx, ‘score and sound design are two separate elements’, although her experimentations with the flutes and the voices sometimes make them hard to distinguish. Vaid, on the contrary, claims responsibility, along with sound designer Markus Krohn – also nominated this year in the new Best Sound Design category – for working closely together. ‘When Chris is stepping more towards death, the composer explains, we realised that it would go further into sound design. […] So we changed the orchestration and instrumentation. […] As a result, the orchestra and the electronic music would cover the deeper frequencies as the music is more emotional, the sound design covering the higher ones.’ And the composer even took it one step further when he asked the orchestra to do this… improvising. ‘It was very difficult to find an orchestra that would be ready to go with us’ but in the end, he got the opportunity to direct the Budapest Art Orchestra, the same that ‘Jóhann Jóhannsson used for Sicario’. ‘My plan was to do 50% based on a written score and improvise the other 50% directly to the picture, using the soundpainting technique. […] That was very funny and risky. Normally, philharmonic musicians would not accept to do that. I made myself a total idiot…’ Or a visionary genius?

To serve the film

Of course, every composer has his/her own story. Irish composer Darren Hendley, nominated for the short film Angela’s Christmas, based on a short story by Angela’s Ashes author Frank McCourt, recalls, about his collaboration with director Damien O’Connor: ‘I draw a lot of inspiration from Damien. […] We have built up a strong rapport when it comes to describing what emotion we want the music to convey.’ Angela’s Christmas marks the fourth collaboration between the composer and the director, Hendley’s heart-warming score accompanying the film with restraint emotion and a masterful writing, although he ‘experimented with different styles of music in the early stages’. ‘The emotion in the music would give the film a strong Christmas feeling without the style needing to be too direct’, he explains. This is the result of detailed discussions and long preparatory work between Hendley and O’Connor, who ‘discussed every single detail of the story’. Angela’s Christmas peaks in a wonderful scene where the main character is in her bedroom with the baby Jesus she stole from the church and sings him a lullaby. According to the composer, ‘This was the first piece of music I wrote for the film as we needed the song finished before the animation team could start the lip sync.’ That was when Damien O’Connor approached Dolores O’Riordan, who agreed to record her version of Angela’s song for the end credits, a few months before the singer from The Cranberries passed away in January of this year. ‘Dolores recorded the song in her studio in Canada and did two takes – one to warm up and the other is what you hear in the film. […] As far as I know, this was the last song she recorded and I’m very honoured I got a chance to work with her.’

When he’s not scoring films ans TV series, Fridolin Nordsø spends time with one of his many indie rock and pop bands. But The Incredible Story of the Giant Pear offered him a new challenge: ‘There’s a lot of music in it, it’s almost as if you have one big, continuous piece of score.’ And Nordsø got involved so early in the project that it got him a little confused. ‘At first I thought it would be great but I was wrong, he says laughing, because I had to redo a lot of the music.’ So, consciously, he began to put himself at the service of the film. ‘It made more sense with the animation, the colours and stuff’, he says.

For a composer, serving a film is often a work that is full of compromises, setbacks and pain, but in the end, always rewarding. When Fridolin Norsø rewrote his score, Dimitra Trypani was daunted by ‘the editing, mixing and mastering part’ for which she was present every day, while Another Day of Life composer Mikel Salas struggled during the composing process with ‘the tension you feel when you are completely focused on trying to control an unstable sound that you’ve generated but can never make again’. Not every composer can enjoy the freedom that Fermín Muguruza’s DIY transmedia project made himself possible to get, but this year’s Emile Awards demonstrate the extremely high quality of the nominated scores, regardless of their country, their composer and the context in which they wrote and recorded them. Because despite all of that, the EAA are slowly building a remarkable quality standard covering a really large spectrum of styles, techniques and horizons in film music. Even we don’t know who is going to win, and we can’t even tell which one we like more.

Written by Valentin Maniglia