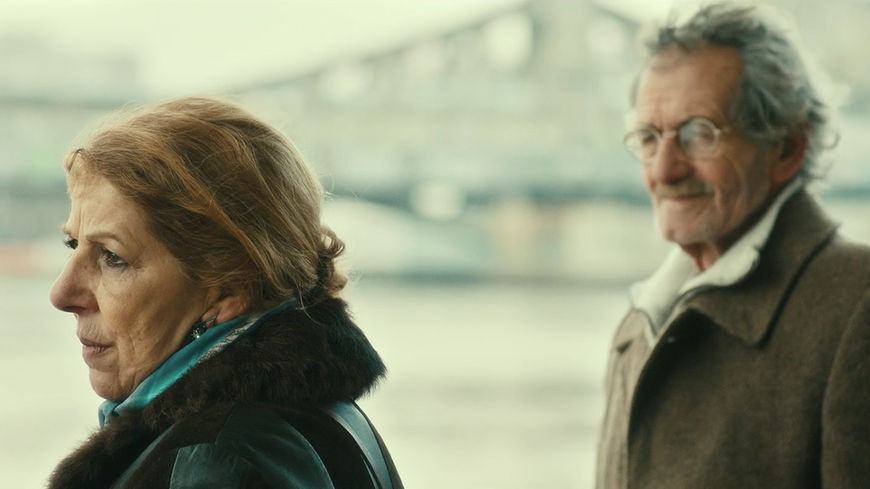

The moving Paris La Blanche is director Lidia Terki’s first feature-length film, with its score composed by Chloé Thévenin. We are invited to follow Rekia, the 70-year-old protagonist, who decides to leave her native village in Kabylie, North Algeria, for the first time. She travels to Paris alone with the hope of finding her husband and bringing him back to their village. But, the man who for the last 48 years has provided for his family from abroad has become a stranger to his family and to himself. Paris La Blanche is a moving story of love and loss, which raises the issues of broken hopes and human sacrifices caused by immigration.

Chloé Thévenin is not your conventional film-music composer. She started out as a DJ under the name Chloé during the 1990s Parisian nightclub scene, and has steadily gained attention ever since, having performed in Europe’s most famous clubs, such as Berlin’s Robert Johnson or London’s Fabric. Chloé has also released two critically-acclaimed albums and a variety of EPs and remixes. In addition to these achievements, Chloé has taken on some unique projects. Her experimental live music shows have seen her performing with striking audio-visual effects. She has also used digital technology to compose music with the audience’s live involvement, and has performed in institutional art spaces such as the Centre Pompidou, Paris.

Chloé has also contributed to film music. Her tracks have been used for Lidia Terki’s short-films (Mains Courantes and Distant).

Score It: In your score for Paris La Blanche, tell us about the use of ambient electronic touches mixed with traditional Algerian music.

Chloé Thévenin: The film takes place between France and Algeria. Lidia Terki, the director, wished to mix these respective music genres. She really wanted me to collaborate with Kabylian musicians (the Kabylian people originate from an ethnic group native the north of Algeria). The challenge for me was to avoid falling into the cliché of two musical genres seeming to play side by side and never making contact. Therefore, I did sound recordings with musicians in advance, converted their textures and then reintroduced them into my compositions. I had to compose themes whilst leaving space for these musicians. They then played until they completely took back ownership of the tracks.

At times the traditional instruments are more present than the others; at other times they fade and are only suggested. It’s a matter of finding the balance.

The film’s musical theme is a song that director Lidia Terki’s father used to play when she was young, which she then learnt to play herself. You brought a subtle electronic touch to this theme, notably through echo effects or the use of lengthy layers of synthesizer.

What do you think of the symbolic significance of mixing these two theoretically very different styles?

This melody Lidia brought to me was THE starting point for the entire film.

It is indeed a tune which Lidia remembers her father playing to her. I really liked this idea of memory. I began with this melody and then rearranged it until it became a track; that’s why I called it Paris La Blanche (like the film’s title). There is a hint of nostalgia in this theme song, which is essential, as it brings a lot to the film’s desired musical direction. I composed the rest of the soundtrack keeping the same instruments used in the theme, whilst continuing to mix them with sounds made by myself and by similar processing. The aim was to find a coherence. Ultimately, the collaboration worked well.

How did you overcome this challenge of working with traditional Algerian (Kabylian) music?

In my compositions, I have often mixed together electronic and acoustic elements. Besides, I was reasonably into rock, punk and folk before getting into the world of electronic music. I immersed myself in Algerian music for the film so I could understand the way the instruments were played, and I discovered a whole world. There is something about Kabylian music which reminds me of techno at times. These two musical styles have something distinctly in common. There were instruments which appealed to me more than others.

Medjoubi Khireddine, a singer-percussionist who plays in the tracks, helped me a lot. He aided me in identifying the instruments I needed. In particular, he called on his friends and musician colleagues, who consequently participated in the tracks: Hadj Khalfa, who plays the zorna (a traditional Algerian wind instrument), and Baazi Mohamed, a great musician who plays the mandole (a Kabylian instrument music resembling an elongated mandolin) and the oud (an Arabic string instrument resembling a lute).

Why did you choose to place film music only at the beginning and at the end of the film? Was this a deliberate decision made by Lidia Terki, linked to the film’s storytelling?

Exactly, it is linked with the narrative: a large part of the start of the film covers the journey made by Reika, the film’s protagonist. Alone, she leaves Algeria and heads towards France, hoping to find her husband who she hasn’t seen in 48 years. We follow her on this voyage, which is an emotional, introspective journey as well as a physical journey. When Reika arrives in Paris, she encounters others on her search, and is consequently more supported and less alone. But she has one sole objective: finding her husband again.

On a slightly more practical level, how did you get in touch with the soundtrack’s Algerian musicians who play the traditional Algerian musical instruments (the oud, zorna, and darbouka)?

Lidia put me in contact with Medjoubi Khireddine, a great Algerian percussionist and singer, who lives in Paris.

As I said earlier on, Khireddine encouraged me to listen to music which could have been of interest to me for the film score. I also listened to certain aspects of the music that I liked to, try and find the instruments which called out to me. Khirredine tried to specify these instruments that I needed. I discovered the zorna, which is a traditional Kabylian instrument. It must be played very loudly and has a very particular sound which comes close to the bagpipes. I thought to myself that I had never had such a loud sound in my studio when Hadj Khalfa (a zorna musician and friend of Khireddine’s) came to play! This instrument had a large presence. However, by processing its sound with echo and delay effects, we could drown its acoustics so that it merged better with the other instruments’ sounds and the general atmosphere. In the end, these instruments naturally slotted into the ensemble.

The resulting integration of the zorna was rather discreet, but it brought a certain tension to the score that we had been missing.

Baazi Mohamed, a great musician of the mandole and the oud, also came to record. I absolutely stuck to the oud, because Lidia maintained that her father played his piece to her on this instrument. However, Khireddine insisted that Mohamed bring his mandole, explaining that the sound would be richer. He was right in the end, because that’s the instrument that we hear the most. Nevertheless, the oud and the mandole are constantly intermixed. This rich experience allowed me to meet very generous musicians.

Paris La Blanche is Lidia Terki’s first full-length feature film, yet it’s not your first collaboration with the director. You have also worked on all her short-films, and she has also directed your music videos.

Lidia and I have actually been collaborating for many years. Some of my tracks are composed specifically for Lidia’s films, and in other instances she has selected tracks from my discography for her work. Similarly, she has directed music videos for my tracks (e.g. ‘Distant‘), and furthermore she gave me the opportunity to use one of her short films (Mains Courantes) for a music video to one of my tracks (‘Be Kind to Me‘) Thanks to her entrusting me with the film score for her first full-length feature film, our collaboration has been allowed to extend. I think it’s a crazy opportunity and experience that I’ve been given.

Do you have your sights set on any other projects with Lidia Terki?

I hope that we continue to collaborate on projects together in one way or another.

Furthermore, Paris La Blanche is your second film score composition after Je ne suis pas un salaud (A Decent Man) directed by Emmanuel Finkiel in 2015. Will this type of project take up more and more space in your career?

Emmanuel Finkiel had proposed that I composed the music for his film Je ne suis pas un salaud (A Decent Man). To do this, he asked me to remake ‘Word For Word‘, a track from one of my albums. He was absolutely absorbed in this track, since the the screenplay and then during the filming and editing process. He just couldn’t tear himself away from the track, and so in the end he kept it.

I am open to all kinds of collaboration where two worlds meet. I collaborated with a poet, Jérôme Game, for a performance at the Casablanca French Institute in Morocco. It was a beautiful collaboration that was an enriching experience. Most importantly, I wouldn’t have necessarily thought of doing the collaboration if it hadn’t been formerly suggested to me. I have just started working on Marie Kremer’s short film. The screenplay and the Marie herself both inspire me, which is a good starting point for the rest of our collaboration together.

In the past, you have often spoken of the sexism which exists in the music industry. How did feel about working with Lidia Terki, a female director progressing in a domain mainly dominated by men?

There are changing attitudes and thoughts, but a certain condescendence still subconsciously (or consciously) remains towards women. This issue isn’t reserved exclusively to one field of expertise or area. Sexism has always existed, exists, and will still exist tomorrow. As for me, I don’t consider music in a different way depending on whether the artist is male or female. It all depends on whether a person’s attitude is based on exchange and respect.

It is undeniable that Paris La Blanche, which deals with issues such as immigration and social marginalisation, brings an underlying political dimension which is both relevant and controversial. How did you apprehend the notion of participating in a film which is so highly topical?

I am not apprehensive; I am very proud to have participated in a film which for once subtly deals with immigration and social marginalisation under a discerning and personal angle. This approach is what makes the film profound and moving. Nevertheless, this film luckily has many interpretations and avoids clichés. It speaks, above all else, about universal values like love and respecting one another.

Finally, as a young female composer, do you have any advice for musicians aspiring to get into the industry?

Try to collaborate with different people and realms; it’s always more enriching than staying in your studio alone.

The full score is available on Soundcloud and via Lumière Noire.

Interview prepared, conducted, translated and edited by Sylvain Pinot and Amalia Morris.

Edited by Marine Wong Kwok Chuen.