Don’t get distracted by the sparkles in his eyes, barely hidden behind a pair of old-school, smoke-tinted glasses: Bertrand Burgalat always keeps a keen look on things. The composer and musician, who started a musical career in the 1980s, likes to play with appearances, as reflected in his ideal-son-in-law, dandyish clothing style which, for a middle-ager, feels like an irresistible disguise for the uncommon life he has left behind. His musical career has always taken a thousand directions, and in that, it is unclassifiable. He founded his own independent label, Tricatel, in 1995 which continues to pursue quite a confidential life, although Burgalat has become some kind of institution for music lovers and a kind of prophet for unusual, outside-the-norm musical projects.

Among his most significant realisations in music—all genres included—are a Depeche Mode remix, arrangements for former The Birthday Party and Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds lead guitarist Mick Harvey, audio recordings of award-winning writers Jonathan Coe and Michel Houellebecq and, more importantly, a wonderful second solo album in 2000—mostly instrumental—The Sssound of Mmmusic, where his interest for film music is as unequivocal as his vintage musical influences which summon the labyrinthine mind of a post-The Beach Boys’ Brian Wilson, the kitsch of an early-days’ France Gall and John Barry-influenced keyboards.

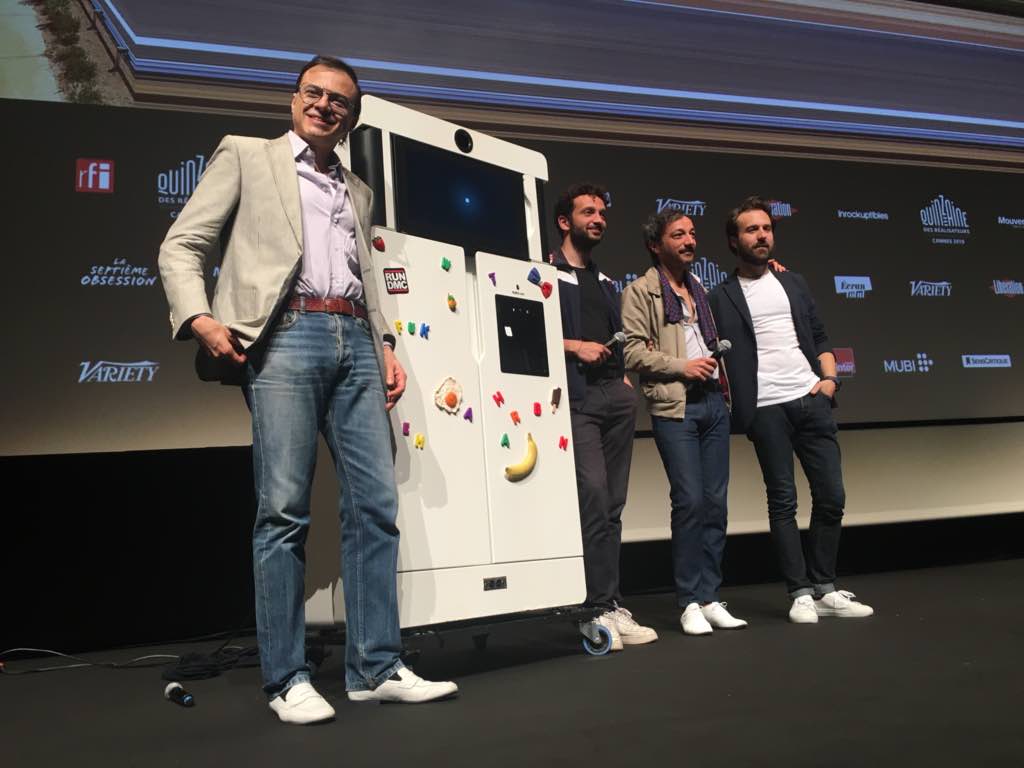

This year, Bertrand Burgalat returns for an eleventh film score, All About Yves, directed by Benoît Forgeard, a French satirical film involving rapper loser Jérem (William Lebghil) whose life is going to take an unexpected turn when he buys an AI-driven fridge named Yves, which was supposed to make his life easier so he can focus on the creation of his first rap album. By some aspects a humourous take on Spike Jonze’s Her, All About Yves premiered at the Directors’ Fortnight in Cannes, where we met Bertrand Burgalat to talk about directors-composers relationships, hip hop and artificial intelligence.

Score It Magazine: For starters, can you talk a little bit about your collaboration with Benoît Forgeard? It is the second time you work together on a feature film but you have known each other for a long time now…

Bertrand Burgalat: I met Benoît in 2012 and we have done a lot of stuff together ever since. We did TV shows like The Ben & Bertie Show, on [French TV channel] Paris Première, which was some kind of musical fiction, with one part written and directed by Benoît and the other where we had music guests. He has directed some videoclips for me, I have made music for some of his TV programs… We did lots of things together. We’re very connected to each other, and it is always my pleasure to get to work with him.

Each of you has his own very specific artistic universe, yet when they are combined together, it all makes sense…

When we work like that, it’s unconscious. I don’t try to push him toward this or that universe, because my music serves his film. I’m being very pragmatic: depending on what he needs, I try to adapt myself.

Did you compose the film’s rap songs?

No, because we thought that those songs had to be as credible as possible. It was important not to compose rap songs that would sound like a parody, and I, in a certain way, would have composed a parody. There is a very precise codification in rap music today, and so it really had to be convincing. It was great to ask Mim and Tortos, who do this in actual life, and so it was important to have them onboard. I did all the rest, including the Eurovision songs, but they did all three rap songs.

Parody is not a dirty word…

Oh, no, for sure, but I think there’s something with rap… I haven’t listened to any recent rap songs or albums, like PNL, and I didn’t want the film’s songs to sound like an advertising jingle. I wouldn’t have done it the way they did it. Maybe I would have tried to compose aesthetic stuff, meanwhile this kind of rap songs have to be very bombastic, very pushy. And there’s something else I wouldn’t have been able to do, which is to coach William [Lebghil] to sing those songs.

Were you involved at an early production stage?

As soon as Benoît told me about the film, I wrote down some ideas. I then took notes when I read the screenplay, and once they edited the film, that’s when you get very specific. But the rap songs had already been recorded, so I started to work from those songs. And when Benoît did the editing, he gave me a list of what he wanted for the score to sound like, which was a very precise list but not too overwhelming. That gave me some flexibility. On the other hand, I never question when or where he wants to put the music, because only he knows when or where the film needs it. Some indications can lose the composer, like “modern,” “timeless,” that bullshit. That’s not going anywhere. But when Benoît gives me suggestions, I know what he means.

Is this distance between the director and the composer important?

Yes. I don’t believe in this, “I’m the director and I know about music” thing. What I like with Benoît is that he’s very concrete. He has a vision. Nothing’s left to chance with him, not in the script, not in the dialogue… If you watch the film on the surface, it can pass for a farce, but his films are actually caustic, they talk about today’s society. That’s why he is so precise. And smooth at the same time. An iron fist in a velvet glove, that’s what he is. I think it’s great. What I expect from a director is for him/her to come up with a vision, and for him/her to express and share this vision with the world. He knows quite well how to do that.

Let’s get back to combination of satire and science fiction, or if I may say, the satire of a close reality, since artificial intelligence can now write music…

Yes, and by the way, I watched the Eurovision final [which was broadcast on May, 18th, five days ahead of the All About Yves premiere in Cannes], and there were robots on the stage! One of the performers, I can’t remember which one—maybe was it the winner?—came up to the stage with two robots touching him while he sang. [The singer he talks about was Chingiz, who represented Azerbaijan, who was undergoing a fake heart surgery by two robots while singing. He ranked 8th in the final classification.] I am a person very negative in nature, but if I have to be positive, what I think would be good is for all of this to force people into doing more unusual stuff. A chord progression, lyrics… You don’t need much GBs of memory to write that. On the contrary, when it comes to many other parameters such as emotion, that’s way more difficult to create or recreate with an AI. But maybe we’ll get to that one day.

William Lebghil in All About Yves, directed by Benoît Forgeard. Original music by Bertrand Burgalat. All rights reserved.

Look: I don’t drink anymore, but when I used to, it was really hard to find a good bottle of Bordeaux without breaking the bank. But then, American critics came and wrote some stuff about that, and that’s why today, you can easily find a bottle of Bordeaux that’s cheap and not bad; what I mean by that is that the situation is stable but what you have in your glass is not that great. So, using the same analogy, maybe AI-created music is going to get better and better with time and technological progress, but it’ll never be brilliant. I think that there’s always going to be a place for a certain type of humanity in music, and that will lead us, composers, musicians, to be more imaginative and less predictable. Musicians—including good, famous ones—tend to be afraid that their audience lose the thread of what’s going on, maybe get bored after a few seconds, as is the custom in music today, and that restrains how songs are being written and composed—a lot. Bridges have become a rare species in songs, now. As for choruses, it has become rare for those to have a chord progression different from the verses. The whole process has become so simplified that obviously, an AI can do that.

The moral being: humans, stop doing what you have learned to do and start getting adventurous to keep original, emotional music alive?

At least, it’s good to try. Consider the amount of films released each year. Now, consider the number of small-budget films among those. I think those films are a fantastic experimentation field for film music! I sometimes regret that auteur films or risky films are not always daring when it comes to film scoring. And yet, there’s a shitload of young, interesting composers today! Any film can have both a small budget and a great score, that isn’t incompatible, and you don’t necessarily have to use prerecorded material as an asset. Okay, Scorsese and Tarantino can do it, but it doesn’t take an existing song to be Scorsese. The score of a film is a very good indicator of the film itself: the way directors and producers consider it says a great deal about what the film’s going to be. I’ve worked with directors and producers who somehow disdained the score, and often, when they can’t handle that, they barely can handle anything. As a result, those films were disasters. Often, bad films feature bad scores. I think that the original music’s worth is an excellent indicator of the finished film. Which is why when Sacem says that film scores have to be reassessed, they are absolutely right. It is in the films’ interests.

Interview prepared, conducted, transcribed and translated by Valentin Maniglia & edited by Marine Wong Kwok Chuen.

N.B.: The interview with Bertrand Burgalat was organised thanks to Les Rencontres de la Sacem.