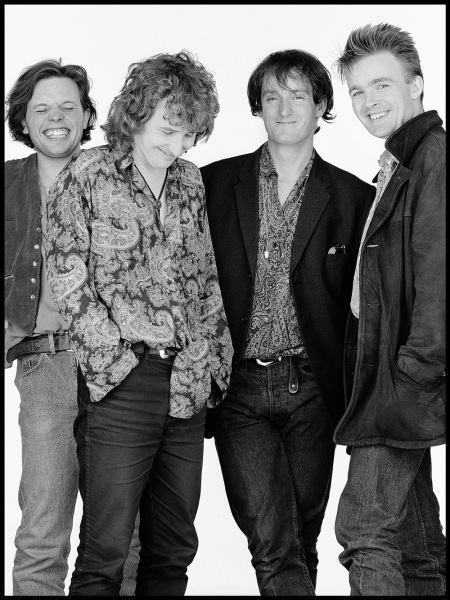

With musical beginnings as a self-taught guitarist, from his late teens Irish composer Ray Harman was in the Irish pop-rock band Something Happens before entering the film and TV scoring world. Since then, Harman has had a rich career as a composer, having written scores for films such as The Young Offenders (2016) and many short films and documentaries such as One Million Dubliners (2014).

Harman’s most recent work includes his score for A Dark Song (2016), an Irish independent horror film, written and directed by Liam Gavin. The plot follows the determined Victoria and her hired occultist, Neil, who risk their lives and souls to perform a dangerous ritual inside an isolated house deep in the Welsh countryside, hoping that the ritual will grant them what they desire. Harman’s score for the film is truly disturbing and deliciously chilling, refreshingly achieved with the utmost simplicity.

With a warm and sincere demeanor, paired with a brilliantly successful career and sheer talent, we had the privilege of speaking with the composer about his musical past and work as a composer.

Score It: Let’s begin by chatting about A Dark Song, one of your most recent scores. Had you watched any witch/horror films for inspiration? Your compositions for this film really reminded us of Mark Korven’s score for The Witch (2015).

Ray Harman: I haven’t seen The Witch. To be honest, I don’t really watch horror films. I find them too scary. Genuinely! But, I love working on them. I looked up The Witch and it looks really interesting, especially regarding the instruments that its composer Mark Korven used. I had only heard about The Witch as somebody else online had mentioned that there is a comparison between A Dark Song and The Witch, just before you had referred to it in your email. I must check it out. The score for The Witch sounds great, and I’d love to get a Nyckelharpa instrument. I can hear the similarities between the two scores. It’s just coincidental though, because I had never heard of it before.

There are elements of primal, sacrificial music in the score for A Dark Song, with the use of drums, wooden instruments and bells, notably evident in the tracks ‘Sealing the House’ and ‘Repeating the Ritual’. This instrumentation evokes the film’s theme of black magic rituals. How did you achieve this primitive sound?

The reason that the director Liam Gavin wanted to use that type of sound was because he wanted to keep the score very primal, repetitive and simple, to reflect the primeval origin of these rituals. We eventually got there. The whole film is about repeating these rituals over and over again. The idea was that, originally, these rituals would have been done with very simple instruments with only two notes, made from wood and goat’s intestines, or something! That’s actually why the score sounds that way. We kept it really simple. Liam wanted to keep the score to just a small number of instruments and groups, so it really was just comprised of only three or four instruments. I used a small group of instruments: the bass, which you can hear, an African drum called a daft, the viola and this north African instrument called a guembri. It’s actually played as a plucked instrument, but if you bow it and distort it, then it has all these odd effects [heard in the track ‘Repeating Ritual’, for instance]. I can’t really play the viola – my main instrument is the guitar – so I had to teach myself how to play it. At the time, I couldn’t hold the viola on my shoulder, so I put the it into a clamp and played it lower down.

http://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zQIzyE9jIgA

Did you get any direction from Liam Gavin, or did he let you do whatever you wanted?

I met Liam at first, and then I had a good chat with him one morning in a hotel for about an hour. I went home, having spoke to him, and put a bunch of demos together of about seven or eight different and very simple ideas. Liam immediately went towards two or three of them that he liked, and he thought the rest were too melodic and had gone the wrong direction.

Were the tracks that Liam selected very different from those he discarded?

Yes. The ones that he liked were very simple, blunt, repetitive and primal. The ones he didn’t like tended to be more melodic and harmonic, and possibly too complex and sophisticated. The score had to be quite simple. With Liam simply choosing those demos, that seared me in the direction I needed to go. That’s the way it always works with film scoring, I think: you fire a bunch of ideas, you get a reaction, and that informs your progress.

How old were you when you seriously got into music? Did you go to music school?

No, I have no formal music education at all. I am self-taught. I picked up the guitar when I was in my early teens. There was a guitar on a wardrobe in our house, left by an uncle. I just enjoyed it; I got a great kick out of it. All through my teens, I was obsessed with guitars and rock bands like Led Zeppellin and Van Halen.

Then, I joined a band when I was in my late teens. We were moderately successful for a while, with a record deal. We toured all over Europe and America, and we had great fun for a few years. That was my first entrance into composing, since we wrote our own material. I didn’t think of it as composing then; we were just guys in a band, we went into a room and jammed. You get a little idea for a track, and you just keep playing it and playing it until it either develops into something else, or it doesn’t. That’s how songs come about in most bands: with a lot of standing around and looking at each other, playing tunes. It’s great fun, though. We were lucky, since we gigged a lot (this would’ve been in the early 1990s). We had one particularly successful album, which was our second record. There were a couple of hits off that: ‘Parachute’ and ‘Blow’. We were busy touring for a long time, for about five years.

Then, in the mid 1990s, we all started to have families. We realised that we either had to try flogging the ‘band thing’, look for other work, or do a bit of both. So, we started to look around for other work to support ourselves, because we didn’t have our record deal anymore.

Was this moment when you transitioned to film music?

It was hit and miss. I always liked the idea of being able to make anything from writing music. One way I sort of did that was by writing music for TV and radio commercials – I thought that was the way to do it. To me, at that stage, film scoring was a bit of a dark art. I wouldn’t have considered it; I thought it was for a different kind of person to me and that it would’ve been way too difficult, requiring proper training. But, I did think that commercials might be easier to do, because the types of music used for them was not a million miles away from what I was doing with the band at that stage. I thought it would’ve been doable with a small home recording studio and so on, so I tried to do that. But, I couldn’t get any work for commercials – none! It was really strange. It’s an odd thing, and I found it difficult to get it.

As I was trying to get work composing for commercials, I got work scoring short films. There wasn’t really much work, and there were often times when I did it for free and for the experience. I really enjoyed it, and immediately realized that I could do it. It was a very slow learning curve for me.

At the same time, I got hired to do a radio show here in Ireland, and that was an interesting, intense school. That radio show was a music quiz, on every week. Each week, the guests would be played four pieces of music, and there would be four questions. I recorded these music pieces. Each one was a well-known song, recorded in the style of another artist. So, you might have a song by Neil Young, played in the style of Michael Jackson. It was mad! You had to somehow deconstruct the song, and then reconstruct it in the style of somebody else. I had do to four of those a week, and they always all had to be done in one day. It was really intense. I learnt a huge amount from doing that, since I did it every week for two or three years. It’s amazing how you learn from just taking something apart, trying to reconstruct it. You had to learn how it was played and how it was constructed melodically.

It sounds like an autopsy!

Yes. For example, if you wanted to record a piece of music in the style of the Rolling Stones in the 1960s, that meant you would have to dig into how recording was done in that period, and and take into account the types of drums, bass guitars, guitars and tuning they use. Therefore, you learn a lot about the actual production of music, mixing and so on. That was brilliant and an amazing Sunday school for me. I learned a lot.

I am still very slow at sight-reading music, but thankfully, it’s become a lot easier because of technology. For instance, you play music in, and then technology enables that you can have it printed out or arranged. Somebody can then send it out to a group of musicians for you, whether they’re string players or musicians for whichever instrument.

I had a couple of lucky-breaks with short films and low-budget feature films in Ireland. The first feature film I scored was called H3 (2001), about the hunger strikes in Ireland during the 1980s. That was the very first feature film I did, and it was really nerve-wracking. To be honest, it was terrifying and very stressful. When I think back on it now, there were a total of 12 or 13 cues in the film – that was all. Nowadays, you do 40 cues for a film, and you think that’s fine. It was a huge task for me the first time. I suppose you have to do those things in order to learn how to do them. A girl called Niamh Fagan gave me a break with H3; she was editing the film and she recommended me. That film was great.

The next lucky break I had was with a feature film called Timbuktu (2004), which was about a guy who gets lost in Tunisia, and his family go looking for him. It turns out that he had been captured by terrorists. That was interesting, because I learned a lot about the scoring approach to ethnic music. Composing for Timbuktu was an interesting task, as the music had to sound slightly North African and also useable as a score.

So, what happens is you get a break with one film, and when people see you’ve done that, there’s a certain level of confidence in your abilities. That confidence rises, and then you get the next job, and you have two films under your belt. It’s as simple as that. Suddenly, people see you and think, “he’s a composer”. That’s sort of how it happens. It’s luck.

Let’s talk about the documentary One Million Dubliners. It’s such an uplifting film, despite its theme of death. The documentary really puts you at peace with this theme, because it is so peaceful. This aspect is reflected in your score, as it’s minimalistic with very few instruments.

I collaborated with the other composer Hugh Rodgers to score this documentary. Hugh was originally asked to score it, and he asked me to come in and help him out, probably because the time was tight on it. Composing for that was done very quickly, actually.

That film was an interesting one to score, because Hugh and I weren’t in the same room. I live in Wicklow and he lives up in Dublin, so we had to somehow make the cues work together. It was a fascinating process, because sometimes he would send me an idea and I would have to incorporate it into one of my cues. For example, the title music is literally one melody by me and another melody by Hugh, sort of mashed together into one tune. In that track, I think it works particularly well.

I do remember there were a couple of really successful collaborations between the two of us, where he would send me the basic melodies, and I would try to put it into a cue and arrange it for pictures.

When we think about Irish music, the kind of music in Lord of the Dance comes to mind, with traditional instruments such as tin whistles and bodhráns. With regard to your score for One Million Dubliners, was the more minimalist style of music a voluntary choice on your part?

Personally, I don’t come from a traditional Irish music background, and it is probably the same case with Hugh. We come from listening mostly to British or American music. Actually, I suppose it would be difficult for me to write a traditional Irish tune. That would require a completely different way of thinking.

Moreover, the film deals with Irish past, but there is no clear ‘Irish’ element in the music.

That never even came up when we were doing the score. At the time, we tried to convey the feel that the editor Emer Reynolds wanted for the documentary, because even though it’s an Irish film, it deals with a universal subject: our own mortality. This subject is what you think about when you watch the film, which is hard to deal with. But, it is a positive film in an odd way, even though it’s about dead people!

You discovered that well-known Dublin historian Shane MacThomais, who had contributed to the making of the documentary, died before the before the it was finished. Did that affect you as a composer?

Yes. To be honest, it was quite a shock and very sad. Shane was the life and soul of the whole film, and its driving force. It was kind of disturbing.

But to be honest, as a composer you forget about those events and the emotion, after a while. What you have is a small task or a particular scene to do. All you want to do is score the scene and situate the emotion that the director wants. So, oddly enough, from repeated watching, the emotional content starts to sit in the background, and you start to forget about it. But now that I think about it, it is still quite a shocking end to the film. He took his own life… It was pretty tough. But it’s a really lovely film.

Let’s discuss your work for The Young Offenders. The humour is so Irish, and the punchlines are hilarious. How was it to score such a fun film?

Comedy is tricky to score, because the specific tone for each comedy film is very precise. You have to get it right in the pocket for each individual film. No two films are the same.

With The Young Offenders, it was really interesting. Peter Foott, the director, was very smart about the music. The two main guys are 17-year-old lads from Cork, in Ireland. They like a particular type of music. Peter informed me that they love jumpstyle music, which I wasn’t even aware of. These clubs in Germany play hardstyle music, but jumpstyle is another subgenre of that, loved by younger people. It has a particular VPM, with a particular way of approaching melodies. Peter said that we needed a jumpstyle-type tune. Jumpstyle has a punchy rhythm, and the idea was that if we got that riff or melody, and if it was useable with a string group, then you would have the tone of the whole film.

I tried out lots of difficult ideas, all roughly in that ballpark.

They were ok, but it took a while to get there. Literally 30 minutes before Peter eventually Skype-called me, I was still trying to come up with ideas for it, bashing around. I came up with that theme just before he called. When Peter heard it, he said that was the one. It did work well with the string group. I marked it up here with strings using my recording system, and then we augmented it. I also got some live players from a college of music in Cork to play on the track, which gives the whole thing a sort of naivety and playfulness. Peter’s main criteria was for the music to be equally useable as a score and to also represent the two protagonists’ silliness in terms of their lifestyle and how they think of themselves. It was quite a tricky bit of tailoring.

That’s what makes comedy a little bit harder, because it has to be representative of what you see on screen. But, you have to be careful not to overdo it; you just have to set up the world and then keep the audience in the bubble for that period of time. That’s easier to do for a horror film for instance, because it’s much easier to go dark with a broad palette. For some reason it’s much more difficult to do with comedy.

Timing is important with all films, but much more so with comedy. The position of cues is imperative: where they start, where they stop, where the changes happen, whether they’re underneath conversations and so-on. It’s fun to do, once you have your melodies and your secondary themes. It becomes easier after a while.

Did you have a say regarding the non-original tracks chosen for the film, or was it purely Peter’s choice?

No, I wasn’t involved in those. Peter had chosen all those songs already.

The opening song is ‘Paper Planes’, M.I.A and the closing track is ‘Where’s Me Jumper’.

‘Where’s Me Jumper’ is a pure sort of Cork anarchy. Its lyrics have nothing to do with what was going on; but the punk-energy and the craziness of it was just perfect.

The randomness of the lyrics feeds the silliness of the two main characters. The last scene was so random and worked perfectly.

The Young Offenders has just been commissioned as a TV series. Peter’s writing it at the moment, and they’ll probably start filming it in the next month or two. I’ll be working on it from the end of the summer. I’m looking forward to working on the series – it’ll be different.

Do you know if some of the cues you’ve already written for the film can be reused, or will you have to create new ones?

I presume I’ll have to work on new stuff. I don’t know yet, to be honest. I would imagine I’d probably have to bring elements of the film that the team are happy with across to the TV series. It’s hard to know. I’m just waiting for my orders from Peter – I’ll do what I’m told!

What’s your opinion on the scoring industry in Ireland at the moment?

The film industry itself is really strong and confident at the moment, going through a great period with fantastic stuff being made. There are great and very inventive filmmakers coming along all the time, making new films.

It’s good that there are more films being made, and the Irish Film Board are responsible for a lot of this energy and confidence at the moment. They have nurtured so many filmmakers and films through the years. The more Irish films that are made, the more likely it will be that an Irish composer that will be hired, and I hope to be at least one of them. There is always something coming up or about to happen that you might possibly get hired for. I’d say it’s a healthy time for the industry, which is small in Ireland.

I was talking to somebody who does the same career as me in New York. The interesting thing about that conversation was that even though there is a huge difference in scale between the industry in Ireland and in the States, we both face exactly the same pressures and exactly the same competitive environment. It’s just a case of scale. But that’s the same everywhere. I don’t mind, as long as I get to pitch for whatever films that are going and being offered.

Do you have any other future projects?

There are a couple of feature films. I’ve just finished a feature film documentary called The Farthest (2017) that has a similar release to The Young Offenders, coming up this summer in the States and in Europe. The director Emer Reynolds made a beautiful film; it’s really lovely. I’m also working on some contemporary dance theatres for an Irish dance company called Liz Roche. In addition, I’m working on a play for the Hadley Theatre in Dublin, and it’s still early days for that. There are always a couple of things going on.

Interview prepared, conducted and edited by Marine Wong Kwok Chuen.

Transcribed and edited by Amalia Morris.