Prepare yourself for your next fix of Netflix binge watching with this musical period drama meets coming of age mythical saga!

Set in the 1970’s South Bronx, The Get Down drags us into a whirlwind of music, passion and creativity, showcasing the turbulent breeding ground of hip-hop culture. The series marks director Baz Luhrmann’s big television debut and he replaces his usual disregard for historical accuracy (we all remember Nicole Kidman and Ewan McGregor singing David Bowie at the top of their lungs on the back of a papier-mâché elephant in fin-de-siècle Paris) with a pursuit of authenticity by appointing rap giants Nas, Kurtis Blow and Grandmaster Flash as producers.

Luhrmann left the score in the safe hands of Gatsby composer Elliott Wheeler. With an impressive alumni of musical collaborations under his belt such as Jay Z, Sia, Nile Rogers, Bryan Ferry and Florence + The Machine, Wheeler has mastered the art of uniting diverse musical styles, genres and cultures into one flawless, coherent vision. Elliott sheds light on his experience composing for The Get Down, working with Baz, collaborating with Nas and Grandmaster flash, recreating the old aesthetics and getting to grips with the history of hip–hop.

Elliott also discusses influences, inspirations and gives insightful tips for aspiring composers!

Score It: How have you found the whole experience working on The Get Down?

Elliott Wheeler: It’s been such an incredible world to dive into. The generosity we’ve had from the community in New York has been incredible. There have been so many people who have been willing to work with us, give up their stories and collaborate on the music. The response that we’ve had from the south Bronx community has been really reaffirming. There is so much responsibility in making sure that we tell the story of this particular time and these particular people accurately, so it’s been wonderful to get the response that we have had.

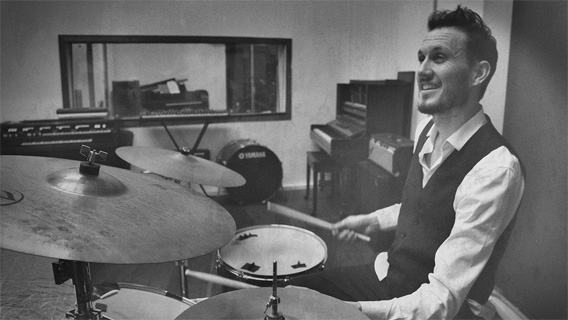

Elliott Wheeler (Source: elliottwheeler.com)

By working on a project like The Get Down, where the music is so integral to the work itself and by working with somebody like Baz Luhrmann, did you feel that your role was more highly valued than in previous projects you’ve worked on? Various composers often feel that their role is undervalued.

EW: The exact opposite. Baz is so focused on music. One of the core edicts we had for the entire production was that we wanted to make sure there were no moments where the characters just suddenly burst into song for no reason. Our rule became that the music had to be so interwoven into the story that if you took the music out, it would cease to make sense. From that regard, we worked very closely with all the departments so it’s one big creative family making the entire show. We all work in the same space: writers are next to the composers who are next to the music supervisors and we are working together constantly. The script will come into effect, then the music, and then we will do tweaks and send that back to the writers, and that will change the music. So in terms of feeling like part of the project, absolutely, it’s been a dream.

You’ve worked on some big collaboration projects such as Gatsby and you’ve worked with some real household names such as Bryan Ferry, Jay-Z and Nile Rogers. How did this big collaboration influence the way you went about creating the score?

EW: We really wanted to present the true music of that era and we’ve been so fortunate in having collaborators such as Grandmaster Flash, Rahiem, Furious Five, Kurtis Blow, Nile Rogers, Grandmaster Caz, DJ Kool Herc, Afrika Bambaataa. We also had some more modern collaborators such as Nas as executive producer who does the introductory narration. It’s an absolutely huge team. So the goal of this collaboration was to bring a sort of tapestry in order to create an overall fabric so that those particular voices can speak in the truest way that they can. At the same time bringing that music into an environment that modern audiences can engage with.

What was it like collaborating with Nas and Grandmaster Flash? Did you get the chance to work with them closely?

EW: It’s been incredible. To start with Flash, he really is, along with Nelson George our historian, the artistic heart of this project. Watching him DJ is like watching somebody play the Stradivarius, the level of control and knowledge he has over the turntables is astounding. We’ve worked so closely together and we’ve developed a wonderful relationship. He is a scientist at heart because he is fascinated now in the same way that he was when he was working out how you actually extend time on turntables. When I actually saw this being done on the turntables and tried and do it for the first time, I was mind blown by the fact that it was just one guy in a room working out the mechanics. He brings this same approach to the scoring. He is fascinated by the process of working out how music changes the interpretation of what happens on the screen. It was interesting for me to watch someone who has so much control over the crowd in a live situation to see how this translates so similarly into what we are doing when working on screen.

What about working with Nas?

EW: Working with Nas has similarly been incredible. He is so appreciative and shows so much respect to the founding fathers of hip-hop. It’s been wonderful to watch these giants from different eras working together on different parts of music. Nas’s facility at being able to take what we are trying to do at a story level and turn that into rap has been mind-blowing to watch. He is such an incredible poet, so quick and so smart and he has his own particular aesthetic which is so different from that of Rahiem or Curtis because it’s from a different era.

With it being such a large collaboration project but also a historical fiction, how much freedom and scope for creative interpretation did you have with regard to composing new material?

EW: It was an amazing journey to be able to go on because we had such a strong foundation point to work on. We were borrowing from that world and it gave us a starting ground to create our own themes and be able to work those themes back into the material on the day. We were blessed to be working with Sony who opened up their entire archives for us. We could just go and ask for the masters and the multi tracks from any of their catalogues. Then we’d take just the baseline from one track and use that as a starting block for building an orchestral score. We would then give it to Grandmaster Flash who would scratch it and create something entirely new from it and then give that to Rahiem or Nas and they’d rap over the top of that. There was such a wealth of material to work from, it was a dream.

Giancarlo Esposito, Baz Luhrmann, Grandmaster Flash, Mamoudou Athie, and Rahiem (Source: Getty Images)

How did you go about deciding when to keep the old classics and when to produce original material?

EW: We really didn’t want people to be able to tell when it switched from one into the other. This is a hallmark of Baz’s style of working. Like with that amazing cover of “Ball of Confusion” by Leon bridges, who is a contemporary artist but did the version in the aesthetics and in the spirit of the original. Or “Heavens in the Backseat of my Cadillac”. It was one of the tracks where we took the original baseline and put it into a track that Miguel produced with Malay giving it a more modern vibe. We wanted the modern viewer to get a sense of what it would have been like for the young characters like Myleene to walk into a disco at that time, at that age, feeling that excitement of being in that new environment. We really wanted it to be a weave between our material, the original material and entirely new creations.

There is such an array of musical genres in The Get Down. There is hip-hop, disco, new jazz, funk, reggae, there is an oriental Bruce Lee/martial arts feel in the scenes with Shaolin Fantastic and Grandmaster Flash, a salsa vibe in the character theme for Francisco Cruz and the Pink Panther theme tune. What was the thought process behind the selection of all these different genres and styles?

EW: What we found in our research was that New York in 1977 had so much going on. It was a bankrupt city: the South Bronx really was burning but this caused a burst of creativity because it forced all of that energy into avenues that exploded into music. Hip-hop was a reaction against disco and its commercialization. 1977 was the highest selling year in terms of albums and that was largely as a result of disco but you also had punk happening and those Puerto Rican flavors. People don’t often realize how much this fed into the hip-hop style as well.

We heard so much about how the Kung Fu aesthetic was part of that early hip-hop breeding ground. When we turned up at the Bronx, one woman came up to Baz and said “my little brother actually thought he was a ninja, he jumped from a three story building”. Kung Fu was where the B Boys took so many of their dance moves. I wanted to reflect that to these young kids, Grandmaster Flash, Kool Herc, Afrika Bambaataa were kings and larger than life stories. Going on a journey across town wasn’t just getting on a train, it was going into a different territory or kingdom. It had this sense of mythology about it and that was something we wanted to accent with that type of scoring. So we looked very much into the music of Lalo Schifrin, Ennio Morricone but also Edwin Starr, Marvin Gaye, J.J. Johnson, Isaac Hayes and Jerry Goldsmith. I wanted to pull those sounds and those aesthetics into the score to reflect this influence.

Did it pose much of a challenge trying to incorporate all these style and genres together?

EW: As a composer, sometimes you sort of look at this tapestry and say “how am I going to pull all of these weaves together?”, but in the end, you just have to trust the basic musicality that everyone responds to. One of the things that I’ve learned through these collaborations is that, generally there is something in every style of music that, if you get it right, the universe will resonate with it and people will get the emotional response. You just have to trust yourself because eventually, there will be something to weave it all together. If you worry about the scope of it too much, you eventually hamstring yourself. You just have to let it flow.

What was the research process like? Did you know a lot about hip-hop before?

EW: It was a combination of so many different elements. You dive in and do as much reading and listening as you can. But with regards to hip-hop, it’s really the conversations you have and people you talk to. The fascinating thing about this era of 1977 is that apart from some very dodgy bootleg recordings, until 1979 when Rappers Delight was dropped, there isn’t a recorded history. So trying to work out what was actually happening at that time is very much an oral history. Talking to the people that were there in the room at the time and ask “Is that what you sounded like?”, “Is this a track you would have played?”. I’d say to Grandmaster Flash “I’ve been reading that you played this track” and he’d say “No no, no, I played that track but not that bit, that’s the whack bit, you never play that part”. It was the same thing when talking to Kurtis and him explaining the modalities of the rhyme and the way it flowed back then. The emphasis was so much more on the first beat than it is now in modern rap and the tonality of the way they were rapping was so much more melodic. It was really an oral education just from talking to these people.

Justice Smith, Elliott Wheeler, Nelson George, Kurtis Blow (Source: Netflix)

Are you a big hip-hop fan now?

EW: Oh even more so! It’s such an incredible art form and the virtuosity you feel when you see these people working and the level of knowledge that goes into creating are astounding.

How this experience compared to other projects that you’ve worked on before?

EW: The sheer quantity of music in this project is unlike anything I’ve ever worked on before. It feels like we’re doing a feature film every single episode. You finish set and you’re already looking down the barrel for the next episode. The work rate is incredible. It’s so satisfying, it’s one of those pinch-yourself-projects that you only get the chance to work on a few times in your career.

Having previously worked on films how was it working with Netflix on a series?

EW: We’ve been extremely lucky with Netflix and Sony. They have been so incredibly supportive. We have such an amazing team, our music supervisor, Stephanie Diaz-Matos and her team have been incredible in terms of the amount of material they’ve licensed and in terms of the amount of fantastic ideas they’ve had. Netflix and Sony have given us a canvas to work on, research to work with, large players to book and just the freedom to create.

You also record your own music. I read that your inspiration for The Long Time came from your favourite scenes from 60s and 70s films. Could you tell us a little bit more about your influences?

EW: I’m a very narrative composer in the way I think about music which is why I’m so drawn to screen composition. I took a break from screen composing and I sat in a room for a long time trying to figure out why I couldn’t write anything and I realized that I always write to stories. So I just chose my favorite stories from American films from the 60s and 70s like Bonnie and Clyde, The Conversation, Three Days of Condor and Chinatown. I’m a massive Jerry Goldsmith fan. It’s an era of cinema that I absolutely love and it has a sound that I’m in love with. So I would just choose a scene and use it as inspiration for a song.

“Baker Man” from Elliott Wheeler’s 2013 album, The Long Time

Do you have a favourite style or genre of music that you like to create?

EW: It depends on what I’m working on at the moment. One of the things about working in music every day is that you do have to find ways to rejuvenate yourself. The line between the project you’re working on professionally and what you then listen to or create for yourself becomes extremely blurred sometimes. When you are in the middle of a project, particularly like this one, you’re just living and breathing it. Sometimes you just need space and silence. To be honest, at the moment, there is so much joy to be had in mining this material, so this is where my head is at the moment. There are other projects coming up but they’re very much over there, I can see them but they’re not quite talking to me yet.

I was just about to ask you about what you’ve got coming up next?

EW: A couple of film projects coming up and a couple of albums coming up which I can’t say too much about yet, but there are other things on the horizon!

Do you have any tips for aspiring composers?

EW: Just do as much work as you can regardless of who the work is for or the quality of the project. Find directors you are excited to work with and do whatever you need to do in order to start working on those projects. When you do the work, just invest everything you’ve got into it, your time, your resources and make every score sound as good as you can. No-one ever listens to anything as a demo, it doesn’t matter how much work you’ve done, or how far through your career you get. If it is people you are not used to working with, finish everything the way you want it to be heard because that’s how they are going to hear it. It’s a competitive game, be humble enough to put everything you’ve got into doing as much score work as you can.

A massive thank you to Elliott for his time and to Teresa Di Martino for helping us arrange the interview!

Interview prepared, conducted, transcribed and edited by Marine Wong Kwok Chuen, Genevieve Stow and Emily Perry.