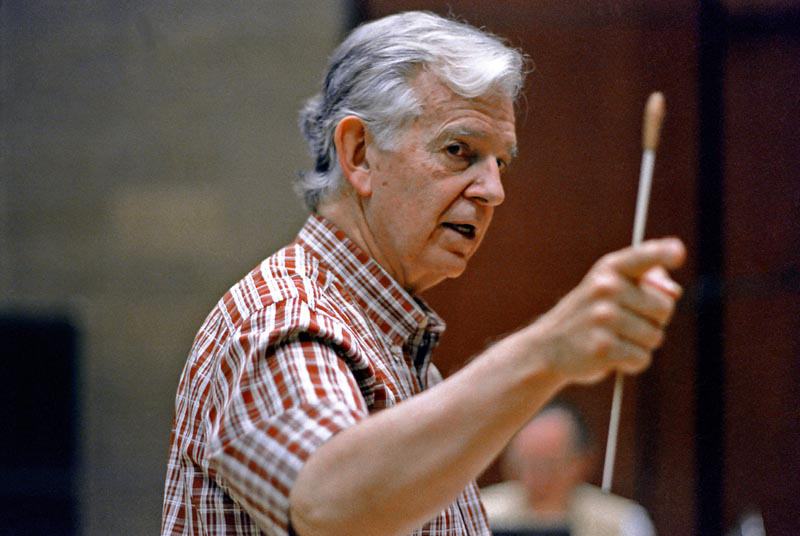

The immensely versatile film composer Bruce Broughton will be awarded this year’s Lifetime Achievement Award of SoundTrack_Cologne on August 26. What better opportunity for Score It Magazine to explore the vast career of this legendary American composer and offer you an exclusive interview conducted by French composer and orchestrator Mathieu Alvado.

To say that Bruce Broughton has left a mark on the screen music world would be no less of an understatement. Born in 1945 in Los Angeles, USA, Broughton has composed an impressive amount of highly acclaimed scores throughout his ample career. The composer has written for every medium imaginable: film, television, video games and the concert stage. His style is equally as varied, ranging from large, symphonic settings to contemporary electronic scores.

Broughton’s film score work has moved generations of film lovers. His first major film score, a broad orchestral canvas for Lawrence Kasdan’s western Silverado (1985), brought him the first of his two Oscar nominations, with the second being for the prize of Best Achievement in Music Written for Motion Pictures, Original Song for Alone Yet Not Alone (2013).

The legendary composer has further written scores for major motion picture such as The Presidio (1988), Tombstone (1993), Miracle on 34th Street (1998), among many others. Broughton continued to make audiences smile through his music, composing for the lighthearted Disney animated feature The Rescuers Down Under (1990) and the comedy hit Honey, I Blew Up the Kid! (1992).

http://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GPWQzq5SQYM

The reason Broughton had initially gone into the movie business was because he had “somewhat of an epiphany”, according to his explanation in an interview with the FilmMusicFoundation. Broughton explains that he was driving in his car at the age of 21 and still in school, trying to figure out what he wanted to do as a career. A song was on the radio, and he was dancing around to the music. Broughton declares that at that moment, he thought: “That’s what I’d like to do. I’d like to make people feel something with music. Within a couple of seconds I worked the whole thing out: movies”.

“I’m not one of those people who watched movies as a kid and loved movie music; I didn’t know beans about movie music. I went to see movies because I thought they were entertaining. I think that actually was a good thing, because I never forgot that people go to watch movies to be entertained, they don’t go to hear the score.”

— Bruce Broughton in an interview with the FilmMusicFoundation, 2014

Besides from Broughton’s work bringing magic to the world of cinema, the composer has also scored for some of the most iconic TV series to date. With 22 nominations, he has received an Emmy award a record of 10 times, most recently on behalf of his score for Warm Springs (2005). His television credits include the main title themes for Jag (1995-2005) and Dinosaurs (1991-1994) and scores for Quincy (1976-1983) and How the West was Won (1976-1979). Broughton has also composed for TV movies such as O Pioneers! (1992), Bobbie’s Girl (2002) and Lucy (2003), as well as the the Emmy Award-winning miniseries True Women (1997).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0AcBK3aMu8Y%20 (

Broughton was also a pioneer in the video game scoring world. He wrote gaming history with his score for Heart of Darkness (1993), the first orchestral score composed for a CD-ROM. As a gifted concert composer, ensembles such as the Cleveland Orchestra, the Chicago Symphony, the National Symphony and the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra have performed Broughton’s works. His musical versatility has allowed his works for wind ensembles, bands and chamber groups to be performed and recorded throughout the world.

Broughton has always remained loyal to his oldest habits as a musician. In the interview, the composer reveals that throughout his career he’s always written his scores on a paper pad. He confides that the good thing about that timeless method is that he doesn’t have to worry about “someone changing what [he] did”. Upon sincere reflection, the 72-year-old composer resolutely declares that he sticks to his traditional pen-and-paper method as it means he would be solely responsible for any mishaps: “If I make a mistake, frankly, I want to fix it myself, because I want to learn.”

A stalwart of the composing community, Broughton has also made a valuable contribution to the domain as ASCAP board member, former Governor of the music branch of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences as well as founding member and president of the Society of Composers and Lyricists. Additionally, he taught and educated the next generation of composers as a university professor at USC’s Thornton School of Music and the UCLA Herb Alpert School of Music.

No matter who we are in this world, it is sheer human instinct to wish that we leave behind a trace of ourselves after we are gone. On being asked how he would like to be remembered, Broughton responds with a twinkle in his eye and a hearty chuckle: “Favourably!”

Well, we can happily confirm that his ideal legacy is probably an accurate prediction.

Mathieu Alvado: You studied music at USC. Was the musical teaching oriented by the proximity of the movie industry?

Bruce Broughton: At the time when I was a student, the USC School of Music was a traditional, academic music school and was not at all oriented towards any sort of commercial music. In fact, the school at that time very much discouraged any sort of commercial writing at all. The university did, however, offer a film music class that was taught by David Raksin, and I took that as my introduction to film music.

Your music is often careful for the brass players. Is this a consequence of your childhood and the Salvation Army’s music program you were involved in?

It’s probably safe to say that my brass background shows in some of my compositions, and especially in scores like Silverado. Although I’m essentially a pianist, I also played horn, and, as a result, was certainly better acquainted with the brass instruments than woodwinds or strings, and understood the technique better. However, no one who writes for orchestra can afford to be single-mindedly biased towards one group of instruments, so I, like many other composers, have had to work over the years to become familiar with and understand how to write effectively for all of the instruments. I still study scores and try to find better ways of making my music sound as effective as possible. Playing in bands and orchestras, however, was very useful experience for knowing how to write for instruments.

As soon as you finished your studies, you got a job at CBS television as a music supervisor. Was it your choice to approach the TV shows more than classical music’s world?

I decided that I wanted to compose music that would move people emotionally. I decided on film music because the music was generally on a scale that interested me – the cues could be very long, emotionally and stylistically varied, unlike songs, which are very short — and because a performance of such music would reach a great number of people. After leaving CBS, I continued working in television and gradually moved into theatrical features, but I never lost my desire to communicate emotionally.

From selecting music for Wild, Wild West, Hawaii Five-O in the late 60s, composing for Dallas or Quincy in the late 70s, for Amazing Stories in the 80s, for Tiny Toons in the 90s or JAG in the 00s, your career seems really bounded to the TV world. From these 40 last years, what do you think about the evolution of the music in this medium?

To my mind, music in TV has on the whole become musically simpler, less emotionally involving and, just as in movies, rather tediously overused. Much of this has to do with the influence of the digital age. Television shows now have temp-tracks; composers have to submit mock-ups of their cues, which means that producers have become more involved in the composers’ creative process and that composers therefore have to spend a lot of time rewriting and tweaking what they’ve written, even though there’s little time (or money) for the process; the budgets for scores have become less, forcing the composers to create their scores in a home studio as well as to become their own music departments.

Television has always been a very quick medium, but with the added pressures of the producers being involved in the actual process of composing, there seems to be a lot less opportunity for originality than there was several years previously. I think this is true of movies, as well. There is an incredible sense of sameness and redundancy in film scores.

Having said that, there are a few composers working in television who are very skilled musically, and who are able to deliver strongly dramatic scores, whether acoustical or electronic.

From Silverado to your concert works I find a link to Aaron Copland and his famous “americana” sound. Is he a strong figure for you?

Not really. Copland invented a unique Americana style, and it’s easy to go to that style when something has to be done that conjures up that mood. If you look in Hollywood’s film scores of the last fifty years, you’ll find lots of composers who have written in a Coplandesque style, especially in westerns: Jerry Goldsmith and Elmer Bernstein among them. However, many countries have similar stylistic associations, even when they’re not entirely accurate to the overall style of the country’s music. It’s common to hear beer hall polkas to represent Germany; a musette accordian to conjure up France; or Elgar’s “Pomp and Circumstance” to stand in for England.

You’ve worked on many “family movies” like Homeward Bound and Homeward Bound II, Honey, I Blew up the Kid or Baby’s Day Out. Some people could think that is movie making without artistic ambition, but I think it’s really hard to find the right “tone” while composing interesting music.

A director told me once that I should not work on comedy, because “no one will see your talent.” In general, people don’t understand that comedy is very hard to do, and, as my director friend implied, whatever art there is in it remains invisible. Many great comedians are actually fine dramatic actors, but the reverse isn’t necessarily true. Whatever art there is in comedy has much to do with timing and, as you say, finding the “right tone” for the piece. It’s easy to ruin comedy by being too heavy-handed, too light or simply in the wrong place at the wrong time. If a film composer believes that the point in composing music for films is to draw attention to one’s “artistic ambition” and have the public notice what one does musically, then such a composer should stick to romantic dramas. In general, a good theme in a romantic drama will be noticed much more than a dramatic or comedic score.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4TIPVT64kVs%20 (

You began your career and worked many years before the appearance of the computers and their domination on the music movie industry. How did you adapt yourself to this new way to compose?

It was sort of like learning a new instrument, except more tedious. Actually, I loved my first experience with computers, because it was the first time as an adult I really had to learn something completely new. I found it very exciting. It was (and still is) often frustrating, but it’s a great tool in the process of composition. I find, however, that if computers are used as the only tool for composition, they’re quite limiting. Often a pencil and a good imagination will get me farther.

As an experienced composer, how do you deal with the American tradition of the orchestrator?

In films, there are generally two reasons why composers are not their own orchestrators. The first is that there simply is not enough time to compose the music and orchestrate it, too. The second is that some composers aren’t very knowledgeable about the orchestra. This has been true since the beginning of film music.

Having said that, I generally do my own orchestration when I have the time for it. I’ve devised a short score format on which I can orchestrate my scores directly as I compose. My “sketch” and my final score are the same piece written on the same page. I’ve done it this way ever since Tombstone, with the one exception of Lost in Space, in which there wasn’t enough time. There were several people who worked on that with me, and I didn’t do any full orchestration at all.

For many years, you’ve been commissioned for concert works. Is it important for a composer who mainly works for movies working without any image? I mean, to find oneself a form for a music which is not imposed by someone else?

It’s certainly important for me to write such music. All film music is accompaniment, which means that in films music is only a part of the total creative experience. Concert music is different in that it is entirely complete and self-contained.

There are many demands and restrictions in film music that one does not find in concert music, and vice versa. For instance, in film music the film itself always determines the form of the music. The scenes dictate not only what sort of music will be composed, but also what the length of the phrases and of the piece itself will be. Additionally, in America, because of the Work for Hire restrictions, the film composer does not have the final aesthetic decision on his own work. In a concert piece, however, the form of the music, as well as all other creative choices, are left to the composer, and all decisions as to the composition are solely his.

Film music is a collaborative medium; concert music, with the exception of opera and ballet, generally is not. I think of myself as a composer, not solely a film composer, and I like to work in as many media as possible. Working for so many years in film and television, I have acquired a substantial compositional technique. In concert music, I have to learn how to put that technique to work for the best expression of my musical ideas. I find that film work helps my concert work and that concert work helps my film work.

Do you think that classical musicians are still condescending to people who work on movies, or is there an evolution of this kind of opinion?

I think that most composers tend to be appreciative of other composers who write well, regardless of the sort of music they compose, and although one may find some condescension or envy at times, there is a greater recognition of the value of film music now among composers than when I was a student.

I think that that estimation may be, however, less true of some (though certainly not all) symphonic musicians, and not necessarily true of some music critics, who often tend to dismiss film music as being artistically inferior to concert music. There are, however, many symphony orchestras in the United States and Europe that have begun including motion picture music in their concerts. The influence of John Williams, who always packs out an auditorium regardless of the orchestra he is conducting, cannot be underestimated.

The truth is that, although there is certainly a lot of very bad music in films, there’s even more bad music (whatever that is) in the concert world. Critics aren’t always very good in admitting that.

You seem to have similar interests as Joel McNeely in recording the music of old masters like Miklos Rosza and Bernard Herrmann. Is it for you, as for Mr McNeely, a way to remind us of the genius of those composers?

I really haven’t asked Joel what drives him to re-record or conduct the music from other composers’ films. I think he simply likes and appreciates the music and wants to make other people aware of it. Jerry Goldsmith, of course, re-recorded some of Alex North’s scores, and I know that Alex’s film work was a big influence on Jerry, as was Bernard Herrmann’s.

In the case of my Rosza and Herrmann recordings, I was asked to conduct these scores by Intrada Records, and thought it would be an interesting project. I liked the music to Ivanhoe and to Julius Caesar, and still do. Some of it is very similar to his concert music. I wasn’t so enthusiastic about the music to Jason and the Argonauts, but the unique and unusual orchestration really intrigued me. It was certainly the loudest score I ever conducted!

Another common point with him is your attachment to teach film composition. What do you think about all these young composers you meet at USC and UCLA? Do you recognize yourself in them?

Although I like teaching, I don’t particularly like teaching film composition, and, except for some occasional exceptions, I try to avoid it. Over the years, I’ve found that the main question young film composers are most concerned about is how to get a job, but they don’t want to find out very much about music.

I’ve noticed also that in the last ten to fifteen years the styles of these young composers have switched from the primary influence of John Williams to that of Hans Zimmer. This doesn’t say too much for their own musical interests, which in my opinion should be much broader. The major advantage in taking a film music course is in learning to adapt one’s music, whatever the style, to the very specific demands of film, which have to do with timing, drama and emotional tone. How to find a job, on the other hand, is a two-minute conversation.

Do I recognize myself in some of these students? Sometimes, especially if they seem particularly confused or naïve, but have a great desire to learn something about music.

What advice do you give to those young composers?

The advice I give is to learn as much as one can about music and become the best, well-rounded composer possible. A film composer will never have enough skill without having to constantly learn something new, because film makes so many creative demands. And then I advise that they take a few courses in psychology. Film music has much more to do with dealing with people than it has to do with music. As difficult as writing music is, it’s often the easy part compared to dealing with the people.

Traxzone will celebrate its tenth birthday. I would like to know what has changed, from your point of view, in film music in the past ten years.

We’re in an emotionally cool period, and music isn’t asked to support the drama in the way that it can. For me, film music isn’t as exciting or as musically involving as it once was. In addition, there’s often far too much music in contemporary films, which deadens the impact of the score. The music itself has become very, very simple, often nothing more than either a series of drones or just a mass of big chords depending on cross-relationships and percussion effects: major, minor, minor, major, boom ta da dum ta da boom ta da dum ta da.

There are a few composers who write very, very well, but often, licensed songs compromise the effectiveness of even their scores. I watched a film recently in which the score had been both skillfully composed and well placed, but the effect of which was almost entirely overwhelmed by the numerous songs that had been inserted all around.

Listen to some of his greatest hits here:

Portrait written by Amalia Morris

Interview by Mathieu Alvado, first published in July 2007 on Traxzone.

Edited by Priya Matharu and Marine Wong Kwok Chuen