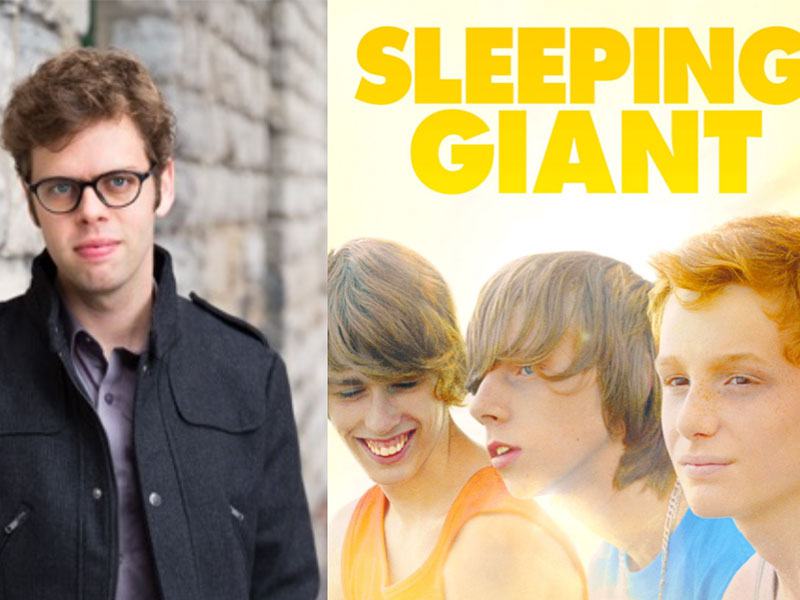

Sleeping Giant (TIFF, Cannes Film Festival) is not another coming of age movie. Canadian director Andrew Cividino follows the lives of three teenagers throughout a summer that will change everything. With tons of compassion, sensitivity and tenderness, he captures the last moments of innocence of Adam, Nate and Riley, three boys just about to be swallowed by the cruelty and unforgivingness of adulthood. The astounding cinematography is accompanied by an extraordinarily brash and spellbinding score by indie rock band Bruce Peninsula and award-winning composer Chris Thornborrow.

Chris Thornborrow took some time to answer a few questions on Sleeping Giant and his work as a composer.

Chris Thornborrow // Sleeping Giant, Andrew Cividino (Canada, 2015)

Score It: You have been working with director Andrew Cividino for quite a long time. How did you two meet and how would you describe your partnership?

Chris Thornborrow: Andrew and I met through a mutual friend soon after I moved to Toronto to pursue my Masters in Composition back in 2006. At the time, I was looking for freelance work as a composer, and Andrew was doing freelance filmmaking. We both cut our teeth in film making doing corporate videos and short films. We were also roommates for a number of years, and are good friends. It makes creative discussions really open and honest.

So how do you collaborate with Andrew Cividino? Do you suggest things or does he tell you what he has in mind?

We do a little bit of both actually. In addition to writing film score, I have a lot of experience creating contemporary classical music, opera, musical theatre, and sound design. I think Andrew embraces that, and allows me to experiment in my process. At the same time, Andrew is an assured director, and is quite clear on the mood/tone he wants to set. There’s really a lot of back and forth discussion between the two of us throughout the whole process.

For Sleeping Giant, you worked with indie rock band Bruce Peninsula. How was your collaboration, how did you “split” the workload?

I was actually a big fan of Bruce Peninsula and so it was kind of thrilling when Andrew proposed to have his film co-scored by myself and the band. A compositional collaboration is something I’d never done before, and I wasn’t quite sure how it would turn out. Andrew proposed that the rugged percussive sounds of the band be used to underscore the monolithic presence of the wilderness, while the subtler sounds of the orchestra and synth pads be used to highlight the psychological states of the three boys.

Neil Haverty (of Bruce Peninsula) and I were writing simultaneously, and we would send each other MP3 demos on a daily basis. By doing this, we were able to incorporate thematic material into each other’s work. Misha Bower (also of Bruce Peninsula) improvised some incredibly haunting vocalises over top of some of my composed tracks. This was such a highlight for me, because I knew what kind of sound I wanted, but it needed to be free. There is no way I’d be able to “compose” what she did so spontaneously in the studio. It truly was a collaborative experience.

Adam (Jackson Martin)

When did you start working on Sleeping Giant? Was it when you read the script, when the film was still in production, when you saw the first images?

I started brainstorming about thematic material and orchestration after seeing a rough cut of the film in December of 2014. I received a fine cut of the film in early 2015, and proper scoring took place over about two months between January and mid February of 2015. It was rather sporadic because at the time I was simultaneously working on a huge, site-specific musical-theatre project called Brantwood, I didn’t sleep much in those days!

One particular thing that differentiates Andrew from other directors is that he gets me involved very early in the process. He would show me early drafts of the script, and bounce ideas off of me before he went to shoot. We spent an afternoon watching raw footage the day after he got back from shooting. By doing this, he gave me weeks of time to brainstorm about instrumentation, mood, and thematic material long before the film is even cut. By the time I’m given a rough cut of the film to actually start scoring to picture, we are more often than not on the same page in terms of ideas. It seems like such an obvious thing to put a composer in the loop as early as possible, and I’m surprised that more directors don’t do this.

When you start things off, do you have a melody in your head, do you go straight to a specific instrument?

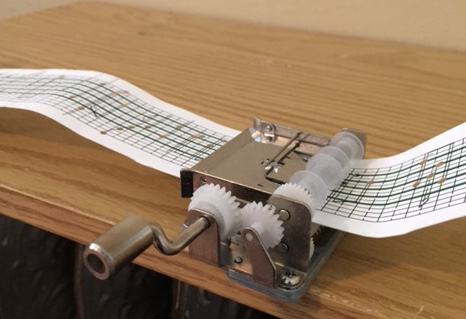

The first thing I do in scoring a film is figure the instrumentation. The palette of orchestral colours I’m using is super important to me. In each film I do, I have to justify why I’m choosing the instruments I’m using to enhance the film’s world. In this case, percussion, harp, reverb/feedback synthesizers, and strings seemed to evoke the expansive space of Thunder Bay, as well as the troubled thoughts of the three boys. I also used a customizable toy music box for the climactic moment of the film. To me, that instrument—with it’s mechanical noises and seemingly naïve tone—speaks to loss of innocence and the indifference of nature to human tragedy.

The theme for Sleeping Giant is terrific : in the beginning, it’s very brash and full of vitality, with the percussion and voices singing the melody. As the tragedy unfolds in the end, it’s subtler, there is this instrument which sounds like a child’s toy and the strings start overtaking, bringing an even darker note to what we see onscreen. I guess it was a way to parallel the loss of innocence. Could you tell us how you came up with this melody and how you used it throughout the film?

So that’s melody written by Bruce Peninsula, and as far as I know, they got it right the first time; it was one of the first tracks they wrote, and Andrew loved it the moment he heard it.

I have a music box where you can write your own melodies using card paper and a tiny hole punch. I transcribed the melody from Bruce Peninsula onto the card paper, and recorded and manipulated it about forty times. I would do things like run the paper through the music box upside down and backwards. I would also manipulate the recordings digitally, reversing them, slowing them down, speeding them up, feeding them through feedback loops, etc. Gradually I built up a thick modal texture of layered music-boxes, then wrote a very clean counterpoint to go underneath with strings and percussion, which we recorded in studio.

The music box (Source: Chris Thornborrow)

Can you tell us about the beginning of your career as a film music composer?

I got into film composition by working with my brother. At the time, I was doing my undergrad in composition, and he was studying animation. I would get my musician friends together and record music for his demo reels. We did some pretty goofy things, and if you do some detective work I’m sure you can find a couple of those videos on Youtube!

Since then, most of the work I’ve done as a film composer has been with Andrew (Ed. note: make sure you check out Andrew Cividino and Chris’s previous collaboration We Ate the Children Last), and a few other film makers/friends here in Toronto. I’m fortunate to be friends with some really creative people in this city, and we’ve really grown together in our respective craft.

From the beginning, I’ve enjoyed a varied career as a composer. I’ve done a lot of short film, but I also compose opera, musical theatre, sound design, and concert music, in addition to being a music educator. I have a broad range of interests in my career, so it’s great to be able to bounce around these different fields of creativity.

Do you see a duality between being a chamber music composer and opera composer and being a film music composer? Or on the contrary, do you think these two activities complement each other?

I would definitely say that these activities complement each other, but my approach to each is quite different. In both medium, music is being used in story telling. In film, music tends to suggest a mood while image leads the story, whereas in opera, music is at the forefront of story telling. The music in contemporary film is generally a very understated thing. A lot of contemporary film music I do is ambient. Hearing my film work on Sleeping Giant, you wouldn’t recognize my operatic and concert-music writing, which is often heightened, explosive, rhythmic and energetic.

What’s the next project you are working on?

I run a concert organization called the Toy Piano Composers and we’re gearing up to host the Curiosity Festival in Toronto in the spring. I’ve written this funky chamber work for this event called Steampunk. I’m also finishing up an electronic opera called Selfie with librettist Julie Tepperman, an unflinching look at the relationship between technology, bullying, and sexual assault. Finally, I’m getting into planning stages for a summer camp I help run with the Canadian Opera Company.

A massive thank you to Chris for his time and detailed answers!

Marine Wong Kwok Chuen