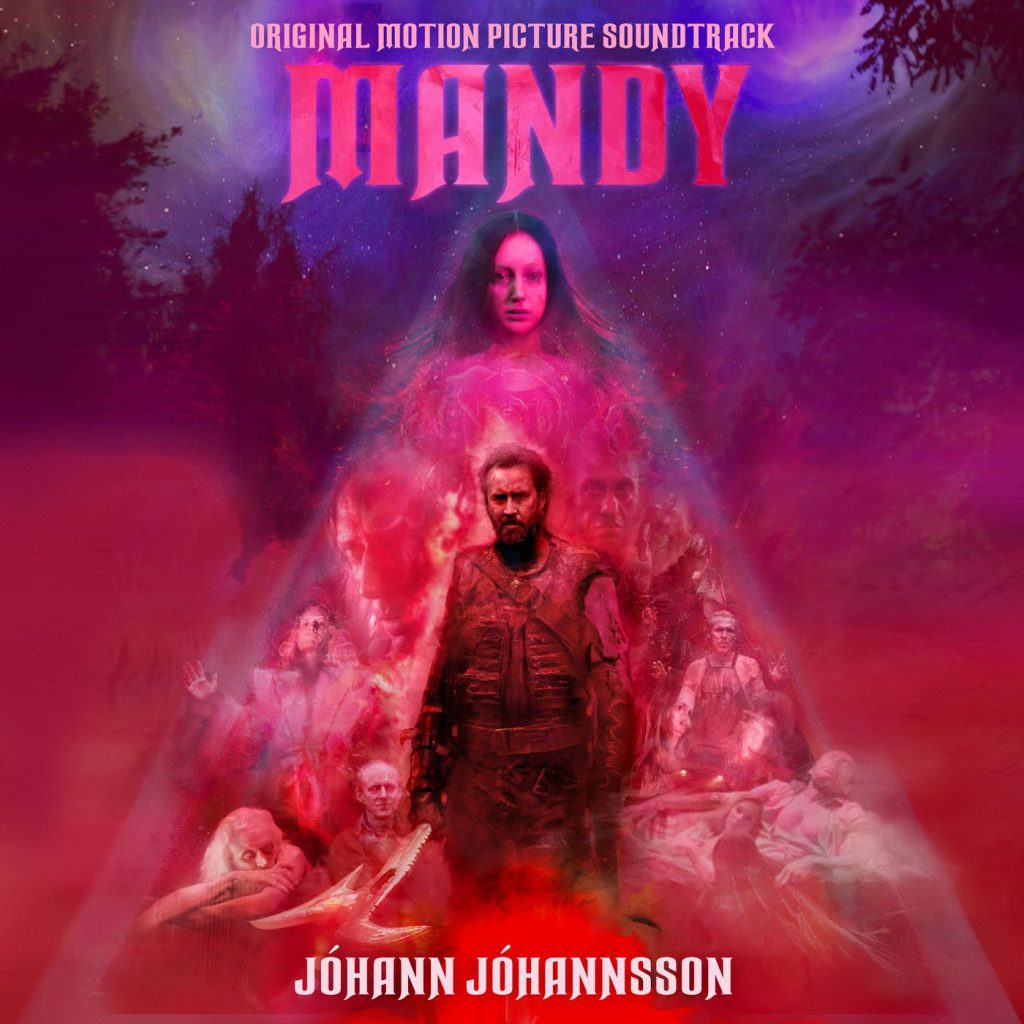

Panos Cosmatos’ sophomore psychotronic madness Mandy is easily one of the best films of the year so far. Set in 1983, the film relates the story of a man (Nicolas Cage) who tracks down the religious cult responsible for killing his wife (Andrea Riseborough). From a very simple and already-seen-before storyline, the film proves to be a nearly unique audio-visual experience which can be compared only to a handful of those other stunning works, such as Nicolas Winding Refn’s Only God Forgives and The Neon Demon, Ken Russell’s Tommy or Sean Byrne’s The Devil’s Candy. Mandy is horror gold, but what makes it even more remarkable is its ability to occasionally step out of the horror genre while remaining profoundly insane. And for that, the film owes a great deal to its score, the last piece of music composed by Icelandic composer Jóhann Jóhannsson, who died of heart failure on February 9th of this year, in his Berlin flat.

Although Jóhannsson, a two-time Oscar nominated composer, has made his trademark out of minimalist, atmospheric compositions, in particular with his three collaborations with Denis Villeneuve (Prisoners, Sicario, Arrival), it is clear that Mandy expesses the composer’s need to explore a new direction. With these last compositions, he blends electronic and live instruments and drowns them under a loud, grim metal soundscape. While the film gloriously reinvents the 1980s horror imagery – the cult, the biker skeletons, the antihero’s desperate vengeance – its score cleverly steps out from the 80s-flavoured film music which has now become a trend. Similarly to The Devil’s Candy, there is a deep connection between on-screen horror and metal music in Mandy, which goes much deeper than Andrea Riseborough’s hair colour and Black Sabbath T-shirt. Through the music comes the expression of pure evil, and it is played so loud in the film that there could not have been a better way to indicate it.

What makes Mandy such a breathtaking score is found in how perfect the combination of Jóhannsson’s mood-based composing style is, with the complex richness of metal music. Coincidentally, Jóhannsson grew up a metalhead in the 1980s and it is something you can tell just by listening to Mandy, in which he instinctively strips out all the genre’s melodic exuberance only to keep the very core of it: distortion, heaviness and dread. Even though he briefly comes back to gorgeous ambient themes, there is always something much darker that lurks behind them: the dreamy synths of ‘Mandy Love Theme’ and ‘Death and Ashes’ come back a few tracks later, in ‘Memories’, only to be broken by distorting noises and sinister breathing.

Yet it is when he ventures into these darker ambients that Jóhannsson’s work flourishes, making the album a stressful standalone experience. Often devoid of any melody, in pure Johannsson style, the score is a major piece of ominous music, demonstrating a bizarre experimentation with notes and noises. He does so with distorted electric guitars in the buzzing ‘Burning Church’ and in ‘Sand’, two tracks that are among the most metal-influenced of the album. He explores horror sometimes in its most refined form with the eerie, looming synths in ‘Starling’ and ‘Red’, some other times with a much crazier instrumentation, like the chilling ‘Black Skulls’ or the terrific diptych ‘Waste’/’Temple’, two tracks that sound like a heavy, desperate satanic incantation and which go hand in hand with the brutal, desperate quest of the film’s main character.

From its beginning to its end, Jóhann Jóhannsson’s Mandy is pretty much a hellish 40-minute doom metal-opera, with the beautiful retro piece ‘Children of the New Dawn’ as its grand finale. The composer himself had planned to record the whole score live with a 9-piece band, which finally did not happen, but still, Mandy remains a powerful moment of pure, heavily discordant and masterfully crafted rock. What Jóhannsson could have further explored in the horror genre, we will never know. But, rather than calling Mandy a testament album, I would rather call it promising, not only for what it delivers to the film itself but also because of how it is a turning point in its own style, firing up our imagination about what could have come next.

Written by Valentin Maniglia, edited by Marine Wong Kwok Chuen