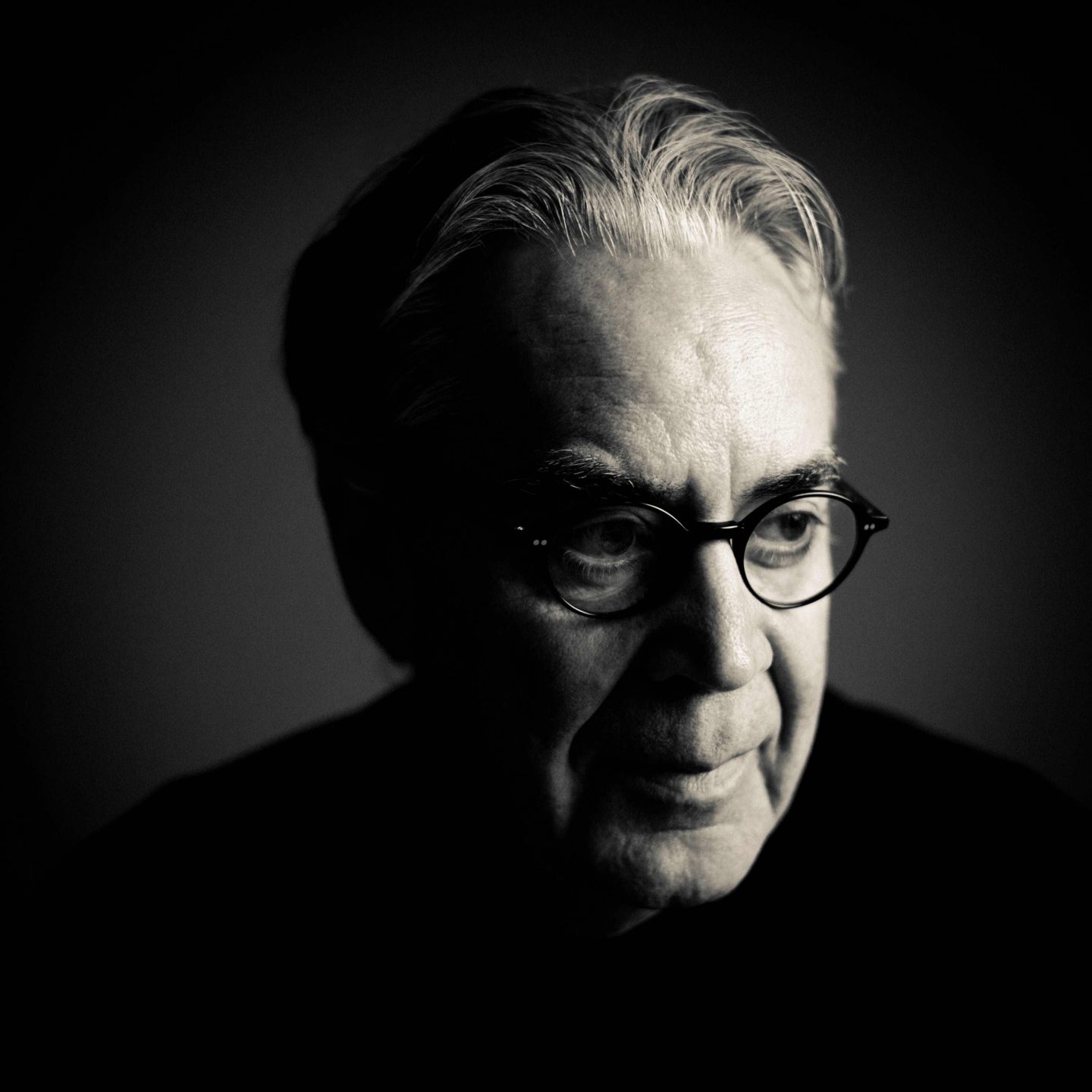

Your list of all-time favourite film scores should feature some Howard Shore pieces. It just has to be. His longest-running collaborations in film brought the Canadian composer to deliver some of the most illustrious film music compositions. For David Cronenberg—he scored all his films since The Brood (1979)—he created haunting, poisonous soundscapes that unmistakably match the themes dear to the filmmaker. Whether they are led by guitars (Crash, 1996), electronic instruments (Videodrome, 1983; Scanners, 1981) or a symphonic orchestra (The Fly, 1986; M. Butterfly, 1993), his scores, just like Cronenberg’s characters, would mutate, reshaped by the film’s final form and genre. Shore and Ornette Coleman’s free-jazz experimental compositions for Naked Lunch (1991) have nothing to do, musically, with the delicately sad score for Spider (2002), yet both delve into the main character’s sick mind and deal with its fateful consequences with a radically different approach. And the same goes on with the rest of their common filmography, with different themes.

For Martin Scorsese—six collaborations starting with After Hours (1985)—he disseminated elements of tango (The Departed, 2006), French folk music (Hugo, 2011) or Irish traditional music (Gangs of New York, 2002) within orchestral compositions. But his best-known collaboration was with Peter Jackson, with The Lord of the Rings trilogy, with a large number of Shore’s pieces becoming instant classics of film music.

Howard Shore’s dark, mind-bending compositions also led him to score Jonathan Demme’s The Silence of the Lambs (1991) and David Fincher’s Seven (1995), two of the most-acclaimed American thrillers of the late-20th century, but noticeably overlooked are his more lighthearted compositions, like his score for Tom Hanks’s directorial debut, That Thing You Do! (1996) or Kevin Smith’s Dogma (1999). Left-out gems like these abound in Howard Shore’s filmography, sometimes hiding even more curious secrets—did you know that Howard Shore composed the original theme for Saturday Night Live, for which he served as the music director for five years, and it is he, in fact, who came up with the name The Blues Brothers for John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd’s band?

As of today, French audiences can discover Howard Shore’s latest work in The Lost Prince, the seventh feature film by The Artist director Michel Hazanavicius. Starring Omar Sy as a single dad who tells his eight-year-old daughter tales before she goes to sleep, the film mixes the story with dream sequences in which the daughter is the princess and the father is the Brave Prince… Until she grows up and eventually falls in love for the first time. Fresh off the Rotterdam Film Festival, where Shore gave a live rendition for a new cut of Crash, we asked him about his fairy-tale-infused score with an unexpected Disney flavour.

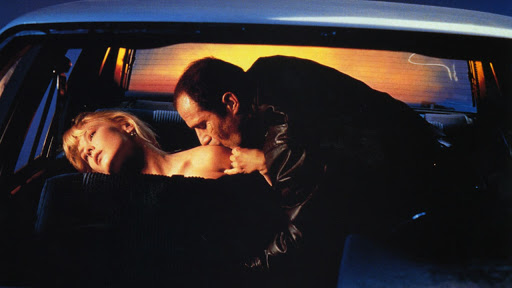

Score It Magazine: Crash deals with provocative and edgy themes, namely an unusual sex fetish. How do you reflect this in your score?

Howard Shore: The score came from a composition I did for the earlier film of David Cronenberg called M. Butterfly. And for that film I’d wrote orchestration for two harps. After the film was completed, I was interested in harp music so I continued and wrote a counterpoint for three harps. So the score for Crash is this really based on this counterpointal composition for three harps. What I did was I had it played on six electric guitars and then added three woodwinds for detail and colour and I had two percussionist to play metallic percussion. So the piece sort of grew away from the film and then I applied the piece to the film in the scoring process.

How do you adapt a score like Crash‘s for a live rendition?

I did a concert piece of Crash in Melbourne, Australia, that I conducted and also in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. And then, for this concert in Rotterdam we added the 40 strings of the Rotterdam Philharmonic. There’s a few themes in the film that are just the strings played on their own, and I was able to, with the help of Mike Schäperclaus, to perform it in Rotterdam. He found the six electric guitars in Rotterdam, worked with them and them up to speed on he piece and then we added the harps, the woodwind, percussion. We built the piece step by step.

That was a real collaboration with Mike Schäperclaus.

Yes. He was the conductor. We had to unarchive the score. We did that in NYC. We worked between NYC and Rotterdam and Mike was the principal person in Rotterdam who worked with us to unarchive the score and then synchronise it to the 4K, fully restored, 10-minute-added new cut film. All of that had to be technically accomplished.

How long were the rehearsals with the musicians between Europe and the US?

The restoration took 3 to 4 months. The rehearsals started about a month ago, with the guitars, and then slowly organised into the last weeks for harps, woodwind, percussion and strings.

Did you discuss this live performance with David Cronenberg?

Oh, very much! He was very excited about it but he couldn’t be in Rotterdam. He did do a video which we played before the concert, a sort of introduction. He’s been involved in it step by step. I also did a live projection concert of his Naked Lunch (1991) in Belfast, Ireland, with Ornette Coleman and in the Barbican in London and in New York.

You mentioned that 10 minutes were added to the new cut of Crash. Did you have to write new material?

Sometimes we had to extend the themes for some scenes which were longer. I had to do some editing some re-creation with James Sizemore and Alan Frey, who helped produce it. We had to go through the process to re-timing the film. A brand new score was created for the Crash live projection concert.

I believe that dialogues have a huge importance for you as a composer, how do you articulate your music, your language and that of the characters on-screen?

I work with the sound of the film. It has more to do with the orchestration, certain tempos that reflect the actions, the dialogues, the editing: it’s all part of the scoring process. First, I start with composition and then I go to orchestration, then to the performance of the recording and then there’s the production and editing of the recording, the mixing.

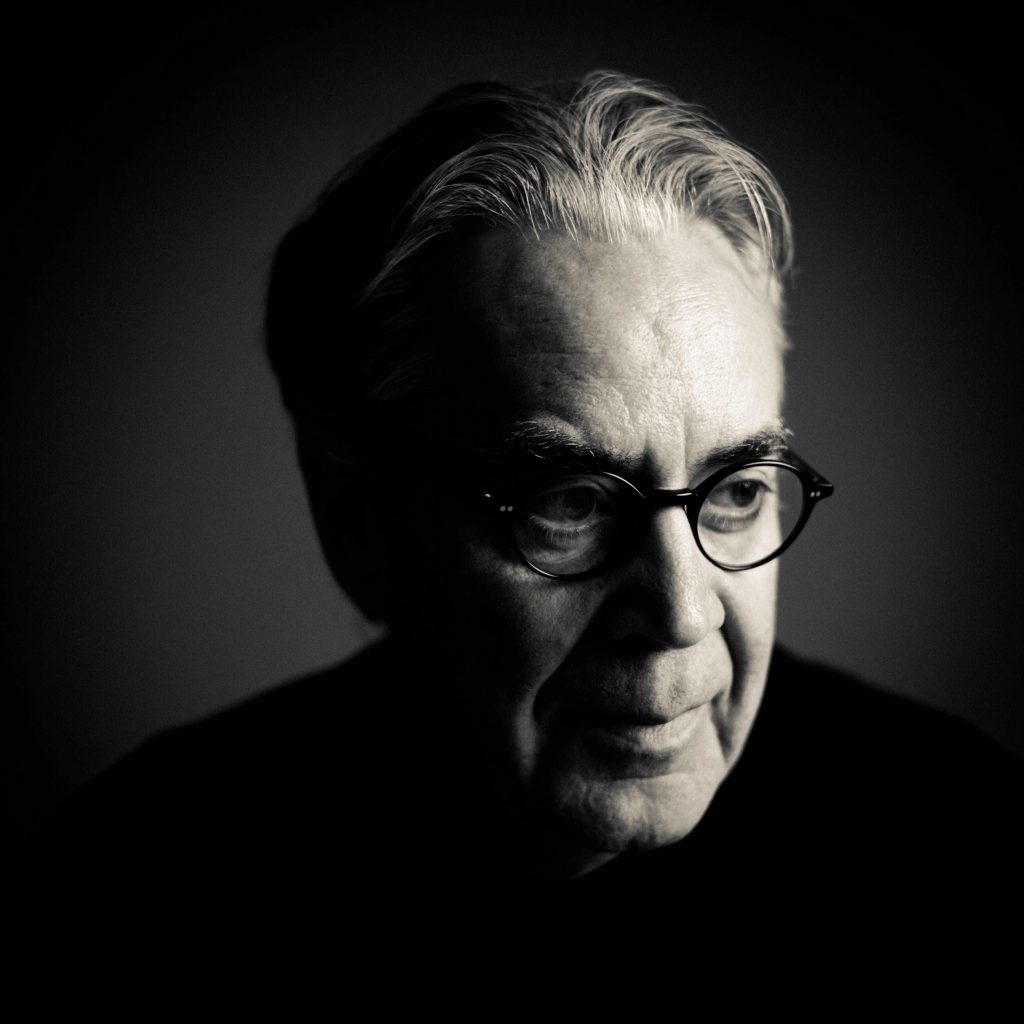

When you read the script for The Lost Prince, what was your first impression?

I enjoyed the script very much. I had previously worked on The Song of Names (2019), for quite a long period. I had just finished this film, so I was very interested in working on this comedy fantasy film. Michel Hazanavicius is a great director, so I was very excited. The script was delightful and charming. I was a single dad as well bringing up a daughter on my own, just like Omar Sy’s character. I related very much to the story, it resonated with me.

I believe that for you the characters and their characteristics are at the heart of your composing process?

I like to work with the actors, I feel close to them when I am composing. In a sense, I get a lot from the acting, the actors’ movements, the way they express their dialogues. I am keen to the acting, especially in this movie. The music has a close relationship with the action.

Did Michel Hazanavicius give you a lot of indication regarding what he wanted?

We worked very closely together, he’s a great collaborator. We’d go back and forth until we agreed. It was our first time together and I hope other opportunities will come! I started working with a rough version of the film, they were in the editing phase, so I started scoring to that. We recorded the score in Brussels with a chamber-sized orchestra.

You were a saxophonist in the band The Lighthouse, are you still playing the saxophone?

I grew up with the woodwinds, the clarinet was my first instrument, the flute, then the saxophone indeed, then I studied the piano, the trumpet and the cello. But over the years, I’ve kept the pencil moving forward, and I’ve put down the instruments… so the pencil has been the main constant ever since I was 9 or 10 years old. The pencil became my instrument and my voice.

So we can’t expect you to play the saxophone on Kanye West’s next album, like Kenny G?

I don’t think so! (laughs) But you can probably find The Lighthouse records and you can hear me play the saxophone!

Many thanks to Valerie Dobbelaere and Garance Desmichelle for their help!

Interview prepared, conducted and edited by Marine Wong Kwok Chuen & Valentin Maniglia.