Peter Nashel truly is a hidden gem among film composers today. Initially a composer in the world of advertising, later on TV where he scored many documentaries, Nashel founded Duotone Audio Group with fellow composer Jack Livesey in 1996, a few years before he came to film scoring with rare but remarkable works. Recently scoring the Netflix series Marco Polo, he talks today to Score It about his score for three-time Oscar-nominated I, Tonya, starring Margot Robbie as Tonya Harding.

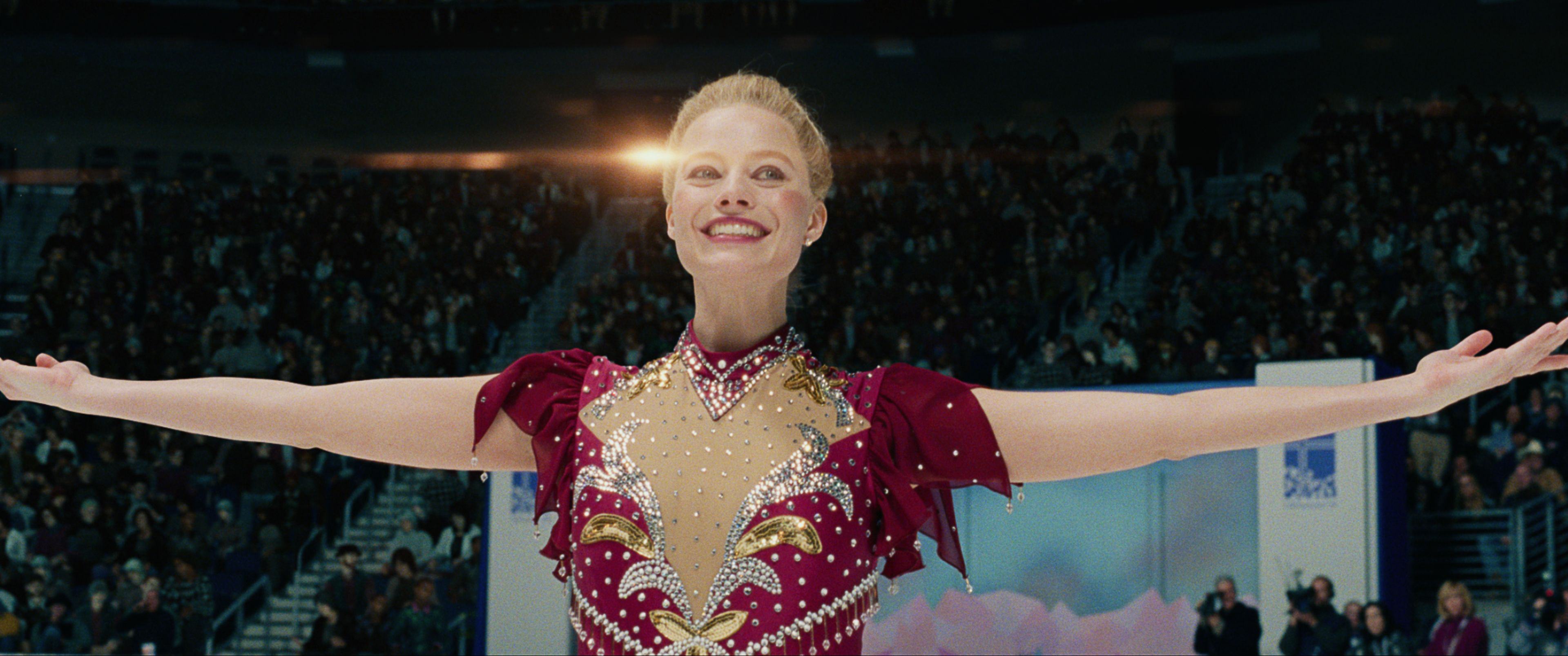

I, Tonya tells the story of the (in)famous figure skater and the events surrounding the attack of Nancy Kerrigan shortly before the 1994 Olympics, in which Harding was involved. Most of the soundtrack is composed of licensed songs, giving excessive energy to the film in the style of Martin Scorsese’s gangster epics. Peter Nashel composed three stressful, dramatic themes which give a haunting dimension to the characters’ actions and the inherent consequences.

Firstly, can you tell me a bit about your background and how you became a film composer?

Actually, I started as a classical saxophone player. I grew up doing this, and when I went to high school and college I started to really get into jazz. So I went from being a jazz musician coming to New York after school and playing around town to doing lots of different plays in lots of different ensembles… Then I got hired to play on a commercial. And you know, at that point, in New York City, making commercials meant… Well, they were really just all jingles, original music that was brand-specific. So this notion that an artist or a group or anybody would ever have their music in an ad was completely foreign at the time. Not only was it foreign, but it had a name: it was called “selling out”. And you would never sell out, like sell soap with your music, that’s ridiculous. So when I met these guys and I played at a session for them, I was really taken with how creative what they were doing was. They weren’t doing standard commercial work, they were doing really cutting-edge stuff like sound collage and very contemporary music. It literally was like an epiphany, I fell in love with it right away. I played them some music that I was working on and they invited me to work with them, so I started to write music for commercials! That was the big turning point for me, because it was my first introduction of music to picture, and it got me thinking. It really started opening up my eyes, as well as my ears, because up until that point, I was a very jazz-centered musician and heard everything through the lens of jazz, which is, if you know jazz aficionados or if you are one yourself, a very high art form. You tend to be very isolated in that world. So, doing my first job for a commercial opened me to a completely new way of doing things, so I continued to do it for several years. Then, an old friend of mine from school was part of this film production company and he invited me to take a look at a cut of a film he was working on, and that was my first feature project, which was The Deep End. That was a big experience for me, and I started to go much more deeply into music for film, music for TV and everything related to that.

You have mostly done music for documentaries and TV projects, so how did you get involved in the production of I, Tonya?

It was through Sue Jacobs, an old friend of mine who was the film’s music supervisor. She called me and said ‘Would you have any interest or any time to take a look at a cut of the film that I’m working on?’ I said ‘Sure,’ and even at the stage when I saw it, you could tell it would be an absolutely incredible movie. I definitely wanted to be a part of it, and that led to conversations with Craig Gillespie, the director. It’s interesting that you mentioned TV and documentaries, because I used to have a manager who said that there’s a curtain that exists between doing music for commercials, doing music for TV and doing music for films. For some people, it’s an iron curtain: they don’t ever go between those disciplines, but for some others, it’s a velvet curtain and they feel free to walk through, and that’s something you see much more now. TV has evolved so much over the last ten years: now it has movie stars, big directors, big writers, and all those people who follow them to these premium TV and streaming projects because, you know, it’s basically a ten-hour feature film. I don’t really see a distinction between the music I’ve done for TV and what I’ve composed for feature films. For me, doing a feature is just part of the normal diet of the musical projects that I’d end up working on.

Would you say that this idea of an iron curtain comes essentially from the world of film? I mean, things are not so different even in Europe, except maybe in the UK or in Italy, but a French film composer would never do music for TV, much less for commercials.

I think it’s more of an artistic mind set. You go where the projects are, where interesting people are working, where interesting projects are created. In the United States, if you’re a big film composer in Hollywood, you typically don’t work on TV, and if you’re a successful TV composer, you don’t work on ads. But that has changed a great deal, now you can see David Fincher doing House of Cards or Mindhunter… Jason Bateman can be on a feature film and on a great TV show like Ozark. The frontiers are much less rigid than they were previously in the US, and I think that brings a change in the art form. For a long period of time before streaming, there was a very specific type of TV entertainment: you had procedural dramas that went week by week. Now, you have that serial type of programming, where you need to start at the beginning and go all the way to the end, and I think it started first in cable with HBO and AMC, and changed them forever… You know, AMC used to be the channel that would do plenty of reruns, like The Godfather saga, James Bond weekends, and all of sudden, Mad Men came and completely changed AMC and now it’s a bona fide powerhouse in the TV industry. Cable in general has become a powerhouse: FX, Syfy, HBO… Their content is incredible. And when streaming services became involved out of necessity, they started to create their own original programs and they had a ton of money. When you work on a project like Marco Polo, honestly, you can’t believe what you’re looking at: they’ve got the best cinematographers in the world, the best costumers, fantastic storylines, amazing actors… This is not a small production, this is giant! It would otherwise have been a feature film, but you’re not seeing it at a cinema, you experience it at home on your own TV set.

Breaking Bad composer Dave Porter, whom we interviewed a few weeks ago for his first score for a feature film, basically said the same things as you are telling me now, and I think it’s fantastic to hear professionals saying, ‘I can do my job differently and I want to experience it, I want to be a part of this change.’

Absolutely! You know, in a sense, a TV advertisement is like a haiku and a television show is a novel that can go on for ten hours, five seasons, seven seasons, eighty hours, a hundred hours… It’s an epic. And a movie – well, that depends on which ones you’re talking about, though – is a bit more like a magazine article. And that’s more the way that people are experiencing it now. There are friends of mine with whom I complain that there’s too much good TV and too many things to watch! It’s like, ‘Oh, you have to watch this, it’s incredible!’ and ‘You have to watch that,’ but you can’t keep up with everything because there are so many things. And frankly, that didn’t even hurt films at all! Look at the crop of films that were out last year or the ones nominated for awards this year, whether it’s Call Me By Your Name or Phantom Thread, I, Tonya for sure, The Florida Project, Lady Bird… This is high art, and it used to be the sole domain of it, but now it has expanded to TV, and when you hear people talk about TV series now, they’re doing it in the same way that they talk about films.

Let’s talk about I, Tonya. How much time did you have to write and compose the score, as you arrived on this production quite late?

Generously, I would say I had about three and a half weeks. Now, in all fairness, there isn’t fifty minutes of score in the film. The score picks up maybe halfway or two-thirds of the way through the film and ends up being kind of a melodramatic character that heightens the actions surrounding the incident. It went very fast because they were trying to get the film ready for the Toronto International Film Festival, which is happening in September, and it was the summer. It was a very quick process that was unusual for me because I didn’t go about it in the way that I would normally go about any of my projects. After I spoke to Craig and after we agreed on what would be the role of the music and how I saw the score playing best in the film, it immediately was just me writing in my studio. And I will give one plug to music for TV and music for advertising: the turnarounds are insane for anyone who’s really worked on these kinds of projects. You know, with Marco Polo, sometimes there were up to thirty-four or forty minutes of music in a one-hour episode, and we – my co-composer and I – didn’t get any more time to do that: we would get a cut, write for four days, submit a preview of the score, we would address concerns, we would have it mixed, and then, we would start over for the next episode. So, you know, your ideas come as much from inspiration as it is about how you’re good at your craft, and I, Tonya was definitely a part of that. With I, Tonya, there wasn’t time for second-guessing: once I’ve figured out what I was going for, I started to write cues, sent them, got feedbacks, and all of that happened very quickly.

How close did you work with director Craig Gillespie?

Very, very close. Craig, Sue Jacobs, editor Tatiana Riegel – who is actually nominated for an Oscar, which is very exciting – and I would sit in a room every couple of days and I would play them cues. Then Craig was off for a while, he went back to Australia where he was shooting another project, so I would send him links to share things and talk about it on the phone. Everything was fully mocked up in my studio for people to see it, hear it and feel it.

Margot Robbie provides Tonya’s moves with something extremely interesting: she can incarnate pure feminine elegance when she’s on the ice, but hints at a whole range of masculine moves in her private life, and this is something that is reflected in the music. Did you take any inspiration from Margot’s performance?

It came much more naturally than that. I wished that I had a master plan so I’d know all along how it would be, but the film has three main elements that are so topical in our world and particularly in the United States now: gender – how men and women treat each other and how women get treated in general – class – high class, low class, red states, blue states… You know, Nancy Kerrigan was a blue-blooded woman from Massachusetts, and Tonya didn’t come from that background. And this story is also a reflection on the whole nature of truth, and that’s something we’re dealing with right now in the US: what is true and what is fake? The film did a great job of creating kind of a Rashomon effect: you have Jeff’s story and you have Tonya’s story, and maybe this isn’t 100% true, maybe it is something they only told themselves or that they took away from the experience. Interestingly, at the time, I actually thought Tonya Harding was the one who attacked Nancy Kerrigan, I never even knew about these other characters. So what I did was writing according to my reaction to the film. To me, it was a very dark comedy: you laugh, but you don’t necessarily laugh at the characters, you laugh with them, except maybe for the character of Shawn Eckhart…

In the case of Shawn, I think you laugh more at the situation he got himself into and how he’s struggling in a most stupid way to get out of it.

Yeah, that’s exactly right. But you know, what I tried to combine musically was to have elements of minimalist music that I think worked perfectly well with her moves on the ice, and inject them this very high drama, the high stakes of it all. Bernard Hermann or Jerry Goldsmith, that’s drama: it was over the top with what was happening.

The film is unexpectedly complex because everything in it relies on contradiction and dualities. What you achieved with your score is adding to these dualities by composing something that is kind of obsessive but not intrusive.

Oh, I’m gonna use that phrase, can I keep it? (laughs)

If you do, please put in on the album’s cover! So how did you create this style, and how did you choose which instruments you were going to use?

I knew that I wanted an element of grace and precision, and almost a feeling of floating or flying between the piano and the strings. And I also wanted to combine that with this whole lot of crazy metallic percussion instruments. You know, given the speed with which everything was happening, the score came together very intuitively. Ultimately, what I settled out was a very small string section which at times is doubled, and at one point I had them not playing necessarily together but almost at battle, the way Nancy and Tonya would be battling. So sometimes, they were synchronized and sometimes they were working independently from each other. There’s definitely a lot of colours with many bowed instruments: bowed glass, bowed vibraphones… The woodwinds also help create this haunting texture. And you know, it’s one of the things that happen when you talk about the marriage between the music and the image: it feels right. It’s animating the right part of the film, and I think this is the real role of composers. At the end of the day, you have to start with one simple question: why does this scene need music? In other words, what can I bring with the music that isn’t already there for a viewer to feel and understand? And when you’ve answered that question, a lot of the score follows naturally from it. A great thing about film music is, it doesn’t have to be in a particular style. I tend to be free from any genre, I tend to choose between different genres in a funny way, and I think it comes up with a much more interesting effect, at the end of the day.

The score also has odd sounds used as motifs like this frantic ticking clock, haunting gimmicks and motifs that defuse the Tonya who’s glorified in the 1st half of the film. And it reminded me of a musical movement that is very “New York”, which is of course minimalism. How important are motifs in your music?

You know, the notion of a theme in film music has evolved a great deal over the last fifty years. A theme used to strictly be a melody, whether it’s a song or a piece of music… John Williams in The Long Goodbye uses the same piece of music over and over with different arrangements, and you can clearly identify this as the theme of the film. I don’t think this would ever go out of fashion, because there’s always a very satisfying place for that in certain types of films. But there’s an alternate language that has appeared… If you take for instance The Social Network, you might not be able to hum the melody as you would do for the theme from The Long Goodbye, but there’s a feel to it that we’re getting from that music. Sometimes it’s a simple chord motif that gets used over and over again, and it’s not even so much of a melody per se but it’s a harmonic progression. And the same thing goes with rhythm: sometimes, people will rely on a rhythmic motif. I think it’s very film-dependent: you’ll have to determine what are going to be the elements that people will hear to establish that consistency in the score. That was definitely something I played with because I, Tonya has so many licensed songs, and so the score had to play this very specific role and be cohesive within that timeframe. There wasn’t so much time needed to come up with a melody, but I think you do walk away from that, and when you listen to the ‘Tonya Suite’ or ‘The Incident’, you’re like, ‘Oh, this is the score I’m hearing,’ because it still holds together as a theme. I think this is part of how themes have evolved over the years. And some filmmakers don’t want themes at all, you know. Michael Mann, for instance… There are pieces of music in his films that work for scenes and then, that’s it! It’s very different from how Steven Spielberg and John Williams work together. You can hear that with Alexandre Desplat, who is one of my favourite film composers today: he has had many very interesting types of scores, some of them thematically heavy from a melodic point of view, some from a harmonic point of view and some from a textural point of view. You know, Syriana is mostly textural to me… The Beat That My Heart Skipped has an eerie score and there’s not necessarily a ton of music, but the way it’s working in the film is so effective, and it’s not traditional film scoring!

Did you work with music supervisor Susan Jacobs in choosing the songs? How did you manage to find and create your own musical space among this myriad of licensed music?

In a sense, the songs operate as the score for I, Tonya as well as the actual score. When I saw the film, there were already a lot of songs, and I thought some of them were out of the league of this film regarding the budget or the artist signoff. This is where the skill and the genius of Sue came in: she was able to reach out to unbelievably huge artists and show them the film and how their music would be used, whether it’s Mark Knopfler or Fleetwood Mac. Sue really was the one that engineered that full part of the film. It didn’t affect me with the score, I think there’s always been some scenes that wouldn’t work with another song and so they needed score. So it was clear which parts of the film I was going to work on and which parts she was going to work on. The first cut that I saw had a whole ton of songs being used, and it was really up to her to get the rights to use them. And she succeeded.

Interview prepared, conducted and transcribed by Valentin Maniglia

Edited by Marine Wong Kwok Chuen